THE THREAT IS REAL. Floods, fires, drought, contamination, poverty, a human propensity for ignorance and willing indifference…

On the surface, the world’s water woes would appear depressingly intractable if not for the international effort by scholars, researchers and conservationists—water warriors such as the team supervised by Professor Rehan Sadiq, the associate dean of UBC Okanagan’s School of Engineering.

Rehan Sadiq

Sadiq has been a specialist in environmental risk analysis and lifecycle management for more than 16 years. Born in Pakistan, he’s familiar with effective means of water delivery—Pakistan (Indus Valley) practically mastered systems for running water about 5,000 years ago. Today, though, more than 80 per cent of people in Pakistan do not have access to healthy or uncontaminated water.

He mentioned this at the first Community Water Forum in November 2017, held at the Innovation Centre in downtown Kelowna. The public forum was designed to provide an opportunity for open, solution-oriented dialogue on topics of shared interest and concern to the Okanagan community.

Sadiq did not disappoint. His impassioned presentation laid out a new plan—rather, a new paradigm: the “One Water Approach.”

“Everything’s connected,” he says. “We cannot view things in isolation.”

7.5 billion people and counting. One billion without basic water facilities or access to drinkable water. One finite water source for all.

Covering watershed management issues—aquatic ecosystems and the role water plays in natural processes, agriculture, recreation and urban development—forum participants addressed worldwide water mis-management and mis-education, which can feel a bit overwhelming, even abstract by its sheer scale. That is, until it hits home: our backyard, the imperfect paradise that is the Okanagan Valley.

“The whole concept is about changing how we manage water around the world,” Sadiq says. “First thing, there is a feeling that we have infinite availability of water. We do not.”

There are huge pressures on the system, he says, noting threats such as climate change, pollution, population growth and high expectations from consumers.

“Water is our most valuable resource. That’s the whole point here. Water is life!”

“So there has to be a more systematic approach. More holistic. With the One Water Approach, there are outcomes.”

UBC Okanagan’s diversified and visionary research extends to all manner of disciplines, from urban water management to source-water protection, asset management and wastewater management, to biosolids-related research that converts water used for domestic, industrial, commercial and agricultural purposes into reusable energy.

“These are all connected,” Sadiq says. “It is a water-energy nexus.”

And it starts here.

Water is Water: Natural choices in the urban water cycle

Professor Sadiq says the One Water Approach is “a paradigm shift that considers the urban water cycle in the same context as we see in the natural water cycle—where water is water.”

Less water from the source—the natural water cycle—means less pressure on the entire ecosystem. That will boost water’s work for, not against, us.

Sadiq is adamant that this approach requires a concerted effort of more accountability, higher standards and an understanding that regulation is not enough.

Twenty per cent of Canadians get their drinking water from a bottle. That adds up to about 2,000 times more than the cost of municipal water.

“What I’m proposing is: Let’s work together, identify where we are based on existing resources, how can we do better, and learn from each other—that is performance benchmarking.”

“It has to be a continuous performance improvement process. It exists in the corporate sector, it exists in the manufacturing sector, it exists in all other industries. Why don’t we treat water the same way?”

Imperfect Paradise: The ‘paradigm shift’ starts here

A tourism mecca and burgeoning business hub, BC’s Okanagan region—defined by the Okanagan Lake and the country’s section of the Okanagan River—is highly impacted by minimal precipitation and high evaporation, making it a paragon of contrast when it comes to water.

“Many may know the Okanagan Valley for its scenic lake views, sprawling orchards and wineries and water-based tourism,” master’s student James Hager says. “Along with residents’ unquenchable thirst for beautiful lawns in a semi-arid region, these activities are putting the future of water resources in the Okanagan at risk.

“With the Okanagan Basin’s seemingly never-ending lakes juxtaposed against the semi-arid agricultural landscape of the valley, an analogy of water scarcity in the region is apparent for those studying ‘Water Resource Engineering’ under Dr. Sadiq.”

The Okanagan Basin has the lowest per capita availability of fresh water in Canada, according to Stats Canada.

One of the biggest questions that Sadiq and his research team are asking is “how can we make sure the quality of the water delivered to consumers is at par or the highest possible level?”

The “very unique challenge” is, that’s not happening, especially in the Okanagan’s cluster of small- to medium-sized communities.

“Our major pitch on this campus is to focus on this specific area. At least from my perspective, I’d like to see more focus on small- to medium-sized municipalities.”

Turning Wastewater into Energy: Pass the Metal Salts

It literally can stink.

When it comes to wastewater treatment, safety and smell is a global concern and now there’s new hope.

Associate Professor Cigdem Eskicioglu and her Bioreactor Technology Group are taking the stink out of wastewater sludge and, in the process, reducing highly corrosive, odorous and toxic volatile sulfur compounds (TVCs) that can severely damage pipes and other infrastructure.

Using common, inexpensive metal salts to increase the digestion of TVCs in oxygen-starved forms of waste, the salts significantly help treat wastewater and recover its resources—energy and nutrients.

“This supports an ultimate national and global goal of energy-neutral wastewater treatment, which can reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” Eskicioglu says.

Eskicioglu says municipal, industrial and agricultural wastewater utilities will greatly benefit and, since publishing their results in 2017, numerous wastewater service companies and industries across Canada and the US have been communicating with these UBC researchers.

In the project’s first phase, the School of Engineering team was led by PhD Candidate Tim Abbott, then a master’s student who wanted to make a meaningful impact in the area of environmental engineering.

Abbott used wastewater sludge from Kelowna’s Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. An NSERC Strategic Project Grant and a UBC Okanagan Research Grant helped fund the project, as did a fellowship from the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey.

Learn more about

Bachelor of Applied Science (BASc): Civil, Electrical, Mechanical

Getting Water Wise: A need for more data, teaching and learning

Common sense is sometimes not all that common. People are notorious for letting faucets run, for using their lawn sprinklers in the rain. And so on.

But Sadiq’s forecast is still pretty sunny about the whole thing, mindful of his esteemed UBC colleagues, partners such as the Okanagan Basin Water Board and opportunities like the Community Water Forum.

He’s also teaming up with UBCO professors Ross Hickey, an economist, and John Janmaat, acting BC Regional Innovation Chair in Water Resources and Ecosystem Sustainability, to look at other angles.

Meanwhile, the roster of water warriors in the School of Engineering keeps on flowing.

Faculty members include Kerry Black, whose cross-disciplinary research includes a focus on sustainable water and wastewater management in Indigenous communities, and Bahman Naser, Solomon Tesfamariam and Kasun Hewage looking at hydraulic modelling of water distribution systems, water asset management issues and lifecycle assessment of urban infrastructure, respectively.

Mechanical and electrical engineers such as Mina Hoorfar, Kenneth Chau and Thomas Johnson are dipping into water-related research and innovation too.

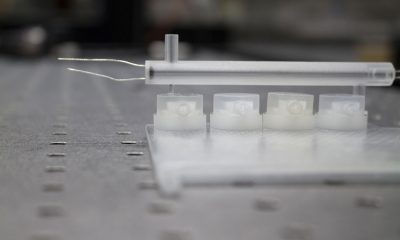

Professor Hoorfar, director of the School of Engineering, recently created a 3-D-printed water-quality sensor. The collaboration began with fellow UBCO mechanical engineering Professor Homayoun Najjaran and a research colleague at Laval University in Québec City.

The 3D-printed interface of the water-quality sensors.

“The entire project was focused on understanding the likelihood of contamination—either through accident or terrorist attack—of purified water inside pipeline networks,” Hoorfar explains. “We wanted to see into every drinking-water network in the city and then get that data to use our software.”

The data can be transferred through a wireless system every five seconds.

Many students graduated through the NSERC Strategic Project Grant that funded the project, and over the past five years many publications have ensued. But Hoorfar is especially proud of the outcome: a low-cost, low-profile water-quality sensor with numerous applications, not the least of which is improving the safety of our drinking water.

Even without tidy little boxes, Sadiq has assembled a world-class team of innovators and integrated thinkers, doers and shapers. And they all share a connection to something precious and profound.

“Water. It has touched our lives in many ways.”