FROM THE TURMOIL OF NATURAL DISASTERS AND CONFLICT ZONES to climates ranging from the heat of the Saharan desert to the sub-zero arctic, Canadian military personnel work in extreme conditions that demand innovative protective gear.

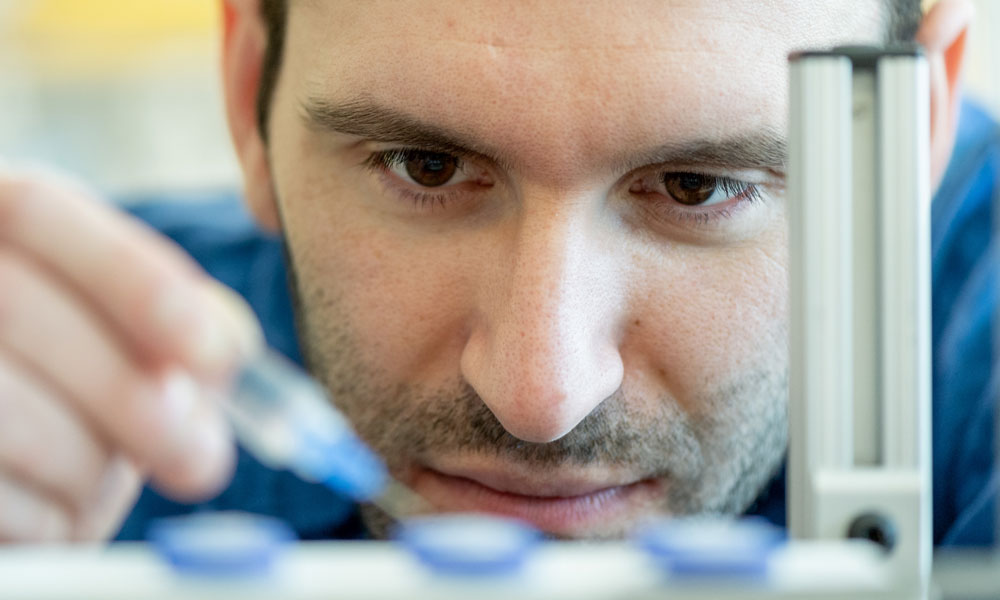

UBC Okanagan Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering Kevin Golovin has assembled a team of the nation’s most esteemed scientific researchers and industry leaders to create and test new textile technologies and body armour solutions for the Canadian Armed Forces.

The network — called Comfort-Optimized Materials for Operational Resilience, Thermal-transport and Survivability, or COMFORTS — involves 11 researchers from the University of British Columbia, two lead collaborators at the University of Alberta and the University of Victoria, and numerous industry leaders in the defence and security sector, including Kelowna-based PRE Labs, Helios Global Technologies, and EPIC Ventures in Victoria.

This broad and ambitious research collaboration will span three years, involve eight ground-breaking research projects, and open up new pathways to innovation in western Canada.

Sweating Bullets

Golovin has a twinkle in his eye when asked about the new high-performance body armour.

“I like hearing people say things can’t be done and doing them anyway,” says Golovin, whose recent research has been focussed on developing ice-resistant materials for the aviation industry.

As the project’s acronym suggests, much of the team’s research is centred around creating more comfortable body armour.

Golovin, who has worked with garment companies Patagonia and Arc’teryx to develop next-generation fabrics, explains that increased maneuverability and overall comfort can be as crucial as ballistic protection.

“Bullet-proof materials weigh down the soldier so much that they may end up in conflict zones longer, putting them in even more danger. It was a process for the Canadian government to realize where the biggest innovations are needed,” explains Golovin.

The Department of National Defence has prioritized a need for protection against more than just the obvious things like bullets and explosions, says Golovin. And it’s this less obvious, non-ballistic protection, where much of the innovation is needed, he says.

“I was recently told a story about a soldier in Iraq who had to keep an IV in his arm to stay hydrated. Of course, that’s not how you want to operate in the field, with an IV sticking out of your arm.”

“I like hearing people say things can’t be done and doing them anyway.”

The Canadian government has invested $1.5 million in the COMFORTS network through a new program called Innovation for Defence Excellence and Security (IDEaS), which supports the development of new defence and security solutions. Additional funding from UBC, MITACS and industry partners brings the value of the COMFORTS network to over $2 million.

At UBC’s Survive and Thrive Applied Research (STAR) hub, a core group of the COMFORTS team are meeting for the first time. Experts from diverse fields, including organic chemistry, kinesiology, mechanical engineering and textile sciences, are gathered around a boardroom table, discussing the evolution of non-kinetic materials.

You Are What You Wear

An assistant professor in the department of human ecology at the University of Alberta, Patrica Dolez is one of the team’s key investigators of materials for non-kinetic protection. She has spent years studying the human aspect of textile science, measuring how what we wear affects all aspects of our lives.

“Up until the 1950s, protective wear consisted mainly of wool, cotton, leather and metal. There was really not much change in terms of materials from the days when a knight hoped he wouldn’t fall from his horse because he couldn’t get back up if he did,” says Dolez.

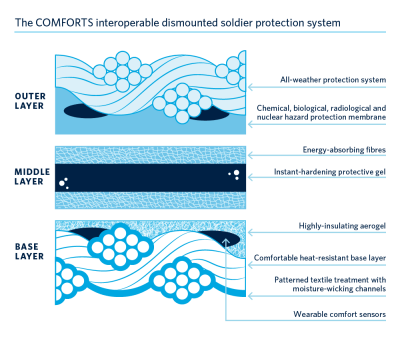

“Next we had polymers, then high-performance polymers, and now we are getting into smart materials,” explains Dolez, who is exploring the use of nanofibres for a layer of the suit that will protect against chemical and biological hazards, while keeping the wearer cool.

“We are developing these next-generation materials to improve protection against all the things that can be used as non-kinetic weapons, while still allowing people to be comfortable,” says Dolez.

“Heat stress is one of the leading causes of death among firefighters. And when we talk about people in the military and people deactivating bombs, they need to be heavily protected. But the thermo-physiological aspect needs to be seriously addressed.”

With the advent of nanofibre technologies, Dolez says, there’s a lot of opportunity to create adaptable garments that keep soldiers safe from heat-stress and extreme cold, while not inhibiting movement.

“Back then, battlefields were battlefields,” says Dolez. “Now, battlefields are everywhere. Where we are going is a place where protective clothing may look like normal clothing and will impair movement much less.”

Dressing in Layers

There has yet to be a single textile developed that can protect from all possible hazards, which is why the COMFORTS solution is taking a layered approach.

Golovin’s expertise with ice-resistant materials will come into play in developing the outer layer — an all-weather textile coating to prevent the adhesion of dust, sand and other solid contaminants.

“Every soldier will wear a base layer. Some layers will be situation dependant. The idea is that all the layers will interface with each other and have real-time sensors to detect how comfortable the person wearing it is,” says Golovin.

Machine learning sensors will be built into the fabric to assess physiological and environmental parameters and trigger alerts for any detrimental changes.

Moisture management and thermal resistance testing for the COMFORTS network will take place at the Apparel Innovation Centre in Calgary, which does standardized testing for the consumer apparel industry.

The Missing Link

Next-generation materials that provide intelligent comfort in extreme conditions are critical to improving survivability in the field, alongside the ongoing need for ballistic protection. The ability to move with greater ease is key to ballistic innovation, explains Jeremy Wulff, a professor of organic chemistry at the University of Victoria.

Co-investigator of kinetics protection research on the COMFORTS team, Wulff holds a Canada Research Chair position in Bioactive Small Molecule Synthesis. He is particularly excited to be at UBC Okanagan where he has access to the STAR Impact Research Facility (SIRF) — a one-of-a-kind ballistics lab enabling him to test the materials he’s created.

“I’m a synthetic chemist. We can produce cross-linkers all day long but I don’t have a ballistics lab to measure their effectiveness. Very few people do,” says Wulff, who carefully explains how materials he developed for the automotive industry don’t melt at high temperatures and are now being used in ballistic protection.

The game changer is the ability to use this cross-linked material to create instant armour that remains flexible, lightweight and breathable until hit by a bullet, explains Wulff.

“People have been looking for a way to cross-link polyethylene for decades because cross-linked materials have higher impact resistance. One of the obvious applications is in the bulletproof vest industry,” says Wulff, who is pleased to report his cross-linked polyethylene performed well in the ballistics lab.

“The thinking was that if we could cross-link the polyethylene in the woven bulletproof vest material, the anti-ballistic performance would either get better or worse. And it looks like it gets better,” says Wulff, who says it takes a lot of ammunition testing to reach that conclusion.

“One of the other big applications for our cross-linked material is as a protective material against knife cuts,” says Wulff, turning to address Dolez who has been listening closely. The wheels obviously turning, Dolez says, “That’s something I can help measure.”

UBC’s STAR Impact Research Facility (SIRF)

The End Game

This kind of collaboration, where overlapping expertise is creating new ways of innovating, is what the COMFORTS network is all about, says Dolez.

“It’s not a question of fitting together,” says Dolez. “I think it’s more a question of finding out what people are doing. It’s like making a recipe; if you are missing eggs, it’s good to know someone else has eggs.”

Wulff has specific outcomes he is looking for with the development of a bulletproof vest, but his affiliation with the COMFORTS team is more about the collaboration itself.

“If we are successful, we will have a prototype of a bulletproof vest that is half the weight. But the COMFORTS project is more about developing a new innovation network,” says Wulff.

Learn more about

UBCO Professor Keith Culver is Director of UBC’s STAR initiative and Innovator-in-Residence at Defence Research and Development Canada. He says the materials being developed have potential well beyond their intended military use.

“I imagine everyone from first responders to soldiers to extreme athletes being impacted by this kind of innovation,” says Culver, who anticipates there will be new technologies ready for field testing within the next two years.

“Technology innovation is a challenging pursuit. These made-in-Canada solutions are being designed to protect those who put their life on the line to keep us all safe. And, we’re just getting started.”