IT’S DIFFICULT TO IMAGINE A TIME when women were not fully considered persons under Canadian law. Yet, this was the reality in the early 20th century.

Canada has a murky past in its handling of women’s rights.

Women were excluded from voting, faced limitations in accessing education, had fewer property rights, and lacked reproductive freedoms through the criminalization of birth control.

Although men and women were declared equal decades ago, many feminists today argue that women continue to face inequality.

One example is the prevalence of sexual violence against women, a reality brought to the attention of millions through the rapid rise of the #MeToo movement.

Enter the women scholars, students and staff of UBC Okanagan. Through their advocacy, education and sharing of personal stories, they’re working to change lived experiences of women in the classroom, workplace and world.

Use Knowledge of the Past to Better the Future

“I like to say there’s always been a women’s movement,” says Alison Conway, professor of Gender and Women’s Studies (GWST) in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS).

Alison Conway

Conway joined the UBC Okanagan community in 2018 after 23 years of teaching at the University of Western Ontario.

“It’s a large and complex subject to teach and research, but it’s so important for everyone to understand where this inequality comes from,” she says.

“I could talk to you about all sorts of gender activism over the past hundred years, but in terms of our modern, western, liberal sense of feminism, the emergence really came in the 19th century, and was largely based around the right to vote,” explains Conway.

Conway has always had an interest in feminist theory, attending graduate school in the 1990s during what she calls an exciting time to be a gender researcher.

“I can remember when Judith Butler published her book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity,” says Conway. “She argued that gender was sort of an improvised performance — and that really started a conversation around how society divides us into one of two categories so early in life,” she says.

Conway’s current research focuses on interfaith marriage and the 18th-century novel, examining how authors of the period approached controversies around faith and authority in narratives about the family.

“What I’m suggesting is the cultural commentary sustained by the novel provides a window into not only our understanding of religious freedom and toleration, but also the status of women in the age of Enlightenment,” she explains.

Conway’s research aims to further understand the history of patriarchal oppression and all its various manifestations, including misogyny, racism and homophobia.

Though she acknowledges Canada has made progress in achieving gender parity over the past century, she’s quick to point out that written law doesn’t always reflect societal norms.

“There are structures of inequality that permeate the way we live our lives, how we organize our relationships,” says Conway.

“Research shows women continue to do more domestic labour than men, and that’s impeding our ability to work longer hours and advance in our careers,” she says, adding that women in the workplace are often discriminated against financially, earning less than male colleagues for equal work.

But it’s not all bad news.

Conway says organizations are amending policies to ensure men and women can equally compete, particularly in academia.

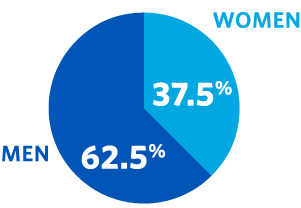

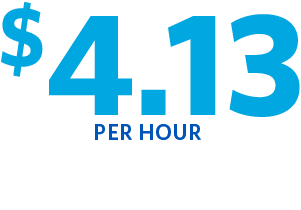

Gender Parity IN CANADA (Stats Can, 2018)

Percentage of men vs. women deans

Number of women workers in Canada’s top 1%

Hourly wage gap between men and women

“It used to be that if having a child in any way slowed you down, the cost could be your career — I don’t think female scholars are as worried about that in 2020,” she says.

This decreased worry is thanks to the implementation of maternity leave provisions at many Canadian universities, including UBC.

Women in tenure-track positions can add a year to their tenure clock, alleviating the stress of balancing scholarship with being a new mother.

“It’s policies like these that force real change,” says Conway.

Conway is optimistic that more change is on the horizon, especially when talking with the next generation of women scholars.

“They’re so smart and so driven,” says Conway, adding that GWST graduates often find themselves in fascinating lines of work.

“Whether it’s social work, teaching, policy or government, they’re particularly well-positioned to analyze the intersectional nature of social identity — gender, race, class — the factors that inform our social lives,” she says.

“I think change often starts by getting the right people into leadership roles. If our graduates can work their way into these positions, there’s no limit to what they can accomplish,” she says.

Image courtesy of Tracy Lee (licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Identify Casual Sexism — and Stop it

One of these future leaders is recent UBCO graduate Tayana Simpson.

Simpson joined UBCO in 2016, intending to focus solely on political science.

While choosing electives, she stumbled upon Gender and Women’s Studies 100, and it got her thinking.

“I was definitely intrigued,” says Simpson. “I’ve always had an interest in women’s issues, not in an academic sense, but in the sense that I’ve always identified as a feminist.”

Wanting to understand more about the politics of women’s issues, Simpson registered and customized her education by incorporating what she was learning in women’s issues into her political science essays.

“I found the two areas of study complement each other very well,” she says.

Simpson still recalls her first GWST class. “It was so empowering to be surrounded by people who felt just like me.”

“Growing up in a small town, I’d been grappling with this feeling in high school that something was off between girls and boys,” she says.

“I knew there was a law that said we were equal, but how could that be the case when girls couldn’t walk down the hallway without boys commenting on their appearance, or take woodworking without having boys suggest they take home economics instead?” asks Simpson.

Simpson credits the #MeToo movement with finally forcing the public to acknowledge the rampant sexual misconduct experienced by women, and suggests the timing of the movement had meaning in itself.

“I think the election of Donald Trump despite his misogynistic attitude scared a lot of women,” she says. “They felt like they were being silenced once again.”

Tanyana Simpson

Simpson applauds women for having the courage to share their stories.

“I think talking about it, particularly with others who’ve experienced it, can really help,” she says.

“I wasn’t at all surprised when I heard the number of women who’d come forward. Most of my university friends and I already knew these experiences were something we shared.”

Simpson considers the movement one of the most powerful forces in modern-day women’s rights advocacy, saying awareness on this level was long overdue.

“We’re half of the human population — that should mean something,” she says. “I feel privileged to know what I know, and now I want to share it with others.”

“We’re all in this together, and I can’t think of a worthier fight.”

You are the Owner of your Body and Experiences

“I think a lot of people think of feminism as hating men, or being against femininity, and I don’t think that’s true or helpful,” says Heather Latimer, assistant professor of Gender and Women’s Studies in FASS.

Latimer joined UBC Okanagan in 2018, and describes her short time here as empowering.

“For me, I still remember being an undergrad student in women’s studies and having ‘a-ha’ moments that radically shaped my view of the world, of myself and of my place in the world,” she says.

“I recall how transformative that can be — I feel so fortunate to have landed at UBCO and to be able to be part of this process for others 20 years later.”

But Latimer isn’t only part of that process for women.

“I’ve had men in my class say they thought the course was just going to be man-bashing — but they were ultimately able to talk about things for the first time in their lives without being judged,” she says, adding that gender expectations for men are also unachievable.

Heather Latimer

Having a small child at home, Latimer says she thinks about the deep socialization boys and girls experience now more than ever.

“It’s something so ingrained in society that you don’t notice it, but if you take a step back, it’s actually quite alarming,” she says.

“You walk through a baby clothing store, and already, there are blue outfits with trucks for boys because boys are supposed to be tough, and pink clothing with flowers for girls because girls are supposed to be sweet — we’re talking about three-month-old bald babies here,” she says.

Latimer points to her past experiences to further illustrate this, revealing she has never held a job outside of academia where she hasn’t been sexually harassed.

“From working in a large corporation to restaurants to a construction company, I was always profoundly aware of my interactions at work as gendered. There were jobs women did, and jobs men did,” she explains.

For instance, in the corporate environment where she worked, “Sure, some women may rise to the top, but the majority of women were assistants,” she says. Latimer points to a deeply entrenched hierarchy that began in the 1960s, when North American women joined the workforce in ‘pink-collared jobs’ that were mostly clerical in nature.

In some of her previous jobs Latimer says there was also inequality in the form of gendered labour.

“My manager would always say, ‘oh, we’re having a meeting — and Heather, can you grab the coffee?’ or, ‘oh, there’s an event that needs planning — Heather would be good at that.’

“The volunteer ‘extra’ work often fell on women employees, and that’s also not okay,” she says.

Though Latimer feels respected in her role at UBC Okanagan, she does note that women faculty members are still tasked with more emotional labour than men at the university.

“I have students come to my office but they don’t want to talk about coursework — they want to talk about experiences in their personal lives,” she says. Although Latimer loves talking to students, she notes these encounters are also about gender. “Because I’m a woman in GWST they assume I’ve developed skills over the years to help — I don’t think men experience this on the same level.”

Latimer’s research areas include reproductive technologies and politics, and reproductive futurism — areas of interest that keep her monitoring American politics closely.

“The day Donald Trump was elected, a friend texted me and said, ‘if you thought you were done talking about abortion, you’re not.’ It was so frightening, but so true.”

“The day Donald Trump was elected, a friend texted me and said, ‘if you thought you were done talking about abortion, you’re not.’ It was so frightening, but so true,” admits Latimer.

“I knew this was a major moment; I knew there was likely going to be amendments to abortion laws because there seemed to be a rise in evangelical conservatism in the States,” she explains.

“All of this indicates the cyclical nature of reproductive politics — we thought this was over with Roe v. Wade, but it’s really not,” she says.

Though Latimer describes herself as ‘one-million per cent pro-choice,’ she thinks both pro-choice and pro-life camps need to stop focusing on the individual and look at reproduction in a larger sense.

“The issue needs to be reframed and we need to think about how to better talk about abortion,” she says.

“We’re seeing this obsessive fetishization of the unborn child, the fetus, and that’s what’s really driving pro-life politics right now in a way that doesn’t match up to what happens to kids when they’re born.”

“They’re fighting for life in one way but not in the other,” she adds.

Latimer says reproductive politics are about more than abortion. “Besides the fact that pregnant people should have autonomy over their bodies, kids have the right to be raised in a healthy and supportive environment,” says Latimer. “Reproductive justice is about the right to have children, the right to not have children, and the right to parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.

“Until people can put religious and political views aside and realize women are intelligent human beings capable of making the right choices for themselves, this issue will never be laid to rest, and that’s a very scary thought.”

Things are Changing — Slowly

Ilya Parkins

“I’ve worked in gender and women’s studies for so long, I don’t think it’d be fair for me to say that being a woman has limited my opportunities in the workplace,” says Ilya Parkins, professor in Gender and Women’s Studies at UBC Okanagan.

“However, that’s not to say I haven’t experienced sexism. Often it’s in the form of being patronized — being spoken down to by men or having my ideas taken without credit — there’s been plenty of that,” she says.

Parkins fell in love with teaching while working as a teaching assistant during her PhD, and joined UBCO in 2007 as this campus’ first GWST faculty member. Though she admits it was a bit lonely at first, the opportunity gave her the freedom to shape the program and learn about curriculum development as a junior scholar.

Thirteen years later the program has grown exponentially, with several full and part-time faculty members, allowing the program to offer majors and minors to undergraduate students.

“I think people on campus are starting to realize the importance of having a GWST program,” says Parkins. “It was a bit more niche in 2007, and now, particularly in the last three to four years, there’s greater interest in understanding the history of how, as a society, we got here.”

Parkins’ research examines contemporary fashion, using fashion as a tool to get to large questions like the relationship of gender and time.

“Women’s fashion has actually been quite elastic over the last century,” she says. “We’ve seen women’s fashion change to incorporate and accommodate signifiers of masculinity, with Yves St. Laurent’s tuxedo suit in the 1960s, and the ambiguous pairing of suits in the 1980s.

“Women’s fashion is an open terrain constantly in dialogue around gender norms. It may appear on one level to be reinforcing these norms, but fashion is all about the moods of the time.”

By sharing knowledge, Parkins hopes to inspire students to think critically and challenge unacceptable behaviour directed towards women.

“Yes, we’re instructing students, but I like to think of it as instructing our future leaders,” says Parkins. “I encourage everyone to consider taking a course in GWST during their time as an undergrad — it will change how they view the interactions they witness every day.”

Science Needs Women

Jennifer Jakobi, a professor in health and exercise sciences, is on a mission to recruit and retain women and under-represented persons in the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM).

Jennifer Jakobi

“I remain, and not for lack of trying by my former supervisor to recruit, the only female PhD student who has graduated under his mentorship, and for years, I was the only woman at the table in my program and school at UBCO,” says Jakobi.

It was a personal experience that led Jakobi to create UBC Okanagan’s Integrative Stem Team Advancing Networks of Diversity (iSTAND) program.

While driving her then six-year-old daughter to school, Jakobi asked what she was doing that day.

“She told me she was going to the explorer’s club, and I asked her what they did. She explained it, and I said ‘oh that sounds like a science club’,” recalls Jakobi.

Jakobi wasn’t anticipating her daughter’s response.

“She told me it wasn’t a science club, and that she hated science because all you do is memorize things, and that science wasn’t important,” Jakobi explains.

“At that moment, as a scientist, I knew I needed to do something,” she says. “She was so young and already decided that she hated science based on what she perceived it to be — drawing lines on paper and grouping and counting specimens,” she shares.

In the weeks following the conversation, Jakobi began to realize why girls were turned off from science so early — they didn’t understand the meaning in it.

“They didn’t understand, why, for example you needed chemistry,” she says. “They didn’t realize chemistry is a part of the toothpaste you put in your mouth and the fabric softener you add to your laundry. I needed to relate it to things they understood, and that’s how iSTAND was born,” she says.

Jakobi launched iSTAND in 2014 as an outreach program aimed at teaching children the meaningful impact of science — but it has since blossomed into so much more.

In addition to youth programs, iSTAND now hosts adult workshops to educate STEM leaders and members of organizations on the importance of integrating and retaining women and minorities.

iSTAND also hosts a podcast series. Episodes highlight concepts related to advancing under-represented persons in STEM while highlighting successes of those in the discipline. The inaugural release recognized a few of the women in STEM at UBC Okanagan and their stories.

“It’s really important that we create and keep opportunities strong for women and under-represented persons in STEM,” says Jakobi.

“We need to embrace the unique views they bring — that’s the most effective way to make permanent change,” she says.

Jakobi is encouraged to see the progress that’s been made in the past decade, but says there’s still a very long way to go.

“I think the times I’m most convinced that things are changing is when I speak to male colleagues who are, say, 10 to 15 years my senior, and they recognize that in order to keep women in the field they need to better understand how to train them,” she says.

“It’s really quite heartening when I see they want to be the best supervisor they can possibly be to this young female because they see her potential and realize the unique obstacles she will encounter,” explains Jakobi.

“Having those conversations, it’s not just men saying, ‘oh I’m married and have kids and two are girls, so I understand women’ — no, that’s not change or an understanding of approaches to inclusivity. When they actually say, ‘I recognize there’s a difference so help me help them,’ then I know we’ve made change because it’s not just tongue-wagging.”

“We need to embrace the unique views women and under-represented persons in STEM bring — that’s the most effective way to make permanent change.”

Jakobi believes this campus’ female leadership, and its male leaders who are genuinely supportive of women, will ensure inclusive opportunities stay strong.

“I’m not sure if all department heads or managers recognize this, but they themselves have the power to make positive change in their area, and positive change is contagious,” she says.

Jakobi points to her former school director, Paul Van Donkelaar, as an example.

“Paul gave me the opportunity and space in my workload to create iSTAND,” she says. “He gave me a chance to see if my idea would work — that’s all most women are looking for: an opportunity to be heard and space to attempt to make change,” she says.

From Jakobi’s perspective, she’s pleased to see more of these opportunities being given on campus and grateful for the support she continues to get from her school to advance kinesiology as a science and underrepresented persons in STEM.

“I really try to be supportive of all ideas,” she says. “If someone has an idea, especially if it’s an inclusive one, I give them a bit of leeway to run with it and see what happens — they’ll either succeed or fail and learn a valuable lesson, but grow as a researcher from either outcome,” she says.

Jakobi is optimistic that this culture of support will continue to be nurtured at UBCO.

“I’m confident that we’re making progress, the gap is lessening because there’s knowledge, and knowledge creates impetus for change.”

Equality, Equity and Justice

“We’re working to create a positive space,” says Jenica Frisque, equity facilitator in UBCO’s Equity and Inclusion office.

“Diversity should be celebrated and embraced — engaging with difference is a hallmark of the UBC experience.”

Frisque works in what she describes as UBCO’s human rights office, dealing with various issues including gender discrimination.

Historically, cases were triaged through Frisque and passed on to the human rights advisor at the UBC Vancouver Equity & Inclusion Office, or to the department head where the alleged incident occurred — but this process has recently been amended as UBCO welcomed its first human rights advisor.

“We’re really excited about this position,” says Frisque. “This makes serving our campus much easier, and I think for a lot of people it’s comforting to know there’s a contact locally.”

Jenica Frisque

Frisque joined UBCO in 2015 and says gender parity — and inclusion in general — has improved during her five years on campus.

“Aside from creating this new position, we have a well-resourced Sexual Violence Prevention and Response Office,” she says.

“Looking at infrastructure, we’re adding more gender-neutral bathrooms, and we’ve added a breastfeeding room, both in the new Commons building,” explains Frisque.

“I also see that more faculty and staff are taking full parental leaves and on a systems level, inclusion is part of the university’s new strategic plan, so I think that’s a lot to be proud of,” she adds.

While Frisque is pleased with UBCO’s progress, she doesn’t think there’s been as much progress on a societal level in the same timeframe.

“Diversity should be celebrated and embraced — engaging with difference is a hallmark of the UBC experience.”

“We still don’t have answers about missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Transgender women, disabled women and women of colour experience disproportionately high levels of sexual violence and we’re still seeing many sexual assault allegations dismissed by the RCMP,” she says, noting that she feels the justice system is pitted against women.

“I’d like someone to explain how they expect women to come forward and share their stories when they know there’s a chance no one will believe them, and the justice system won’t protect them,” she questions.

“It’s really frustrating to see blame put on women for not coming forward sooner when people don’t understand the repercussions of each individual speaking out — it could result in the loss of a job, housing, put immense strain on interpersonal relationships — it’s very complex,” she says.

Frisque, who is currently on maternity leave herself, continues to advocate for inclusivity at all levels, sharing her vision for the future of UBCO.

“Universities are places of learning and transformative change.” she says. “For me, my goal is to figure out how to build on our differences to transform this campus into a place where everyone is thriving.”