‘I LOVE THE HEART’ IS DR. RYAN WILSON’S RAISON D’ÊTRE: the mantra that keeps him going. A postdoctoral research fellow with UBCO’s School of Nursing, Wilson’s passion for all things cardiovascular first blossomed during his time in the emergency department (ED) nursing patients.

“Chest pain is one of the most common reasons people visit the ED,” he explains. “Although the volume of these visits has decreased in recent years, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are still the number one cause of death globally.”

CVDs collectively refer to conditions that affect the heart and the body’s blood vessels. Causes can include structural abnormalities of the heart or blockage of the vessels, which in turn can lead to heart attacks and other significant diseases, such a stroke. The most common type of stroke is due to a blockage of blood vessels in the brain.

More than 2.4 million Canadians live with diagnosed heart disease, meaning they not only face a reduced quality of life, but they must also shoulder costs associated with lost work, hospital visits and specialized care. Stroke, a possible consequence of heart disease, is also a global leading cause of mortality and disability; an estimated 400,000 Canadians currently live with its effects.

It’s easy to understand then, why researchers like those at UBC Okanagan are committed to finding new treatments and improved diagnosis and care options that will deliver better health and quality of life.

heart disease in Canada (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012/13)

Number of Canadians aged 20+ with diagnosed heart disease

Second leading cause of death among Canadians

Men are twice as likely to suffer a heart attack than women

Lessons from the Great Apes

For Dr. Rob Shave, understanding how healthy systems work is the first step to unraveling what goes wrong in disease. The professor and director in the School of Health and Exercise Sciences is studying how a healthy heart responds to different types of exercise and environmental stress.

For this, Dr. Shave has taken an evolutionary step backwards by comparing the human heart’s malleability with our closest ancestors, the great apes. “Apes share 98 per cent of their DNA with humans and, perhaps more importantly, heart disease is also their most common cause of death.”

As part of the International Primate Heart Project, Dr. Shave collaborated with Dr. Daniel Lieberman, professor of human evolutionary biological sciences at Harvard University, and Dr. Aaron Baggish, director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at the Massachusetts General Hospital Heart Center.

The team compared hearts of wild born chimpanzees with groups of men who had a wide range of physical activity levels. Some men were sedentary but disease-free while others were highly-active, including subsistence farmers from Mexico, resistance-trained football linemen and endurance-trained long-distance runners.

As part of the International Primate Heart Project, researchers compared heart function in chimpanzees, gorillas and humans.

From the athletic stadium to wildlife sanctuaries in Africa, the team used non-invasive techniques to measure heart function and then correlated this with physical activity, or a lack thereof. They also examined the effect of exertion on the heart’s structure.

The landmark study showed that the heart is malleable and responds to the body’s demands. “Ape hearts are adapted for short, sharp bursts of activity like climbing and fighting,” explains Dr. Shave. “Their hearts are rounded and the chamber has thick walls, which allows them to respond to sudden, brief spikes in blood flow.”

Compare this to the human hearts that underwent moderate-intensity endurance activities like walking and running. In humans, the left ventricles were larger, longer and more elastic, allowing them to handle high volumes of blood.

“But, when the [human] heart experienced a pressure challenge produced by weight-lifting or high blood pressure, this stimulated thickening and stiffening of the left ventricular walls,” Dr. Shave adds.

“Our hearts adapt and change to the physical demands placed on them.”

He notes that in humans, there is a trade-off between these two types of adaptations. People who have adapted to pressure challenges cannot cope as well with volume changes, and vice versa. That means that the hearts of endurance runners are less able to accommodate a pressure challenge, while a weight lifter’s heart will not respond as well to increases in volume. Dr. Shave’s study also suggests that when our hearts don’t get exercise, they start to negatively ‘remodel’ themselves, potentially leading to heart problems later in life.

“Overall, these findings indicate that our hearts adapt and change to the physical demands placed on them,” Dr. Shave explains. “The best way to keep them pumping is to keep active, and to always include some endurance exercise.”

Broken Hearts

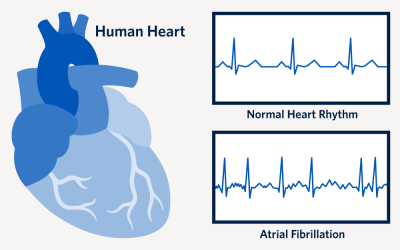

Atrial fibrillation (Afib), or irregular heartbeats, frequently lands people in hospital. While the causes of the disease are unknown, high blood pressure, diabetes and an unhealthy weight are all contributors. More concerning, however, are the complications.

“Compared to those without Afib, patients with untreated Afib have a five-fold increased risk of stroke and three-fold increased risk of heart failure,” says Dr. Wilson. “What’s more, many individuals don’t realize they have Afib and are unaware of the danger.”

Strokes happen when blood flow to the brain is interrupted and brain cells — ultimately deprived of oxygen — die. This can result in muscle weakness, difficulty talking, memory loss and cognitive or emotional problems.

“Seeking early diagnosis of Afib is critical to reducing stroke complications,” Dr. Wilson adds. “Treatments are accessible, inexpensive and simple. The key is to know you have it.”

Currently, more than 15 per cent of those over 80 years old have Afib, yet many people aren’t aware of the condition, its symptoms or consequences.

Dr. Wilson, a self-described patient advocate, wants to improve this. One of his first studies questioned patients after their Afib symptoms became bad enough for them to finally seek treatment. “I wanted to know their story. Surprisingly, a lot of them knew something was wrong, but they attributed symptoms like fatigue and shortness of breath to normal aging.”

Not only is enhanced disease awareness a solution, but so is increased screening. Dr. Wilson is optimistic about the use of technologies such as smart watches, but adds there is still a role for old-fashion medicine.

“We can encourage people to take their pulse daily and note changes like unusual rhythms,” he says. “But, when people don’t feel well, they should seek advice. In the end this comes down to patients taking responsibility for their self-care, which will ultimately lead to improvements in their lives.”

Dr. Wilson is hopeful his work will encourage more individuals to seek early treatment, reducing the incidence of strokes and hospital visits, while also improving their quality of life.

“Afib is a global issue, and strokes are a horrible consequence of this treatable condition.”

Life After Stroke

In 2012, Jennifer Monaghan, a 43-year-old mother of two, was enjoying a fulfilling life. But one day when she tried to talk to her husband, no words came out. Sheer panic set in a few minutes later when she couldn’t move the right side of her body. Paramedics took her to the hospital where she was diagnosed with a stroke and stabilized with medication.

After a month-long stay in hospital, Monaghan was a changed woman. She continued to have problems moving the right side of her body, a common condition after stroke, and speaking was an effort. Although she received excellent care and rehabilitation while in the hospital, she continued to experience stroke symptoms after returning home.

“It was a bewildering time,” she says. “I didn’t really know what a stroke was and why this happened to me. Also, once I left the hospital I had very little external support. My world was upside down. Suddenly going from running a household to being the one needing care is very disorienting.”

Thankfully Monaghan’s mother was able to help with child and house care while Monaghan started her long path to recovery. After many failed attempts, she eventually found a physiotherapist and speech pathologist who had expertise working with stroke patients.

Jennifer Monaghan and her family.

“Unfortunately, anecdotes like Jennifer’s are all too frequent,” says Dr. Brodie Sakakibara, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Occupational Science & Occupational Therapy. “Patients receive exceptional care in the hospital setting but once they return home, there are few community-based options to help continue the recovery process.”

He adds that these patients are at high risk for secondary strokes or other conditions like heart attacks.

Dr. Sakakibara, who is also a researcher with the Southern Medical Program’s Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Management, hopes to empower patients to manage their health and well-being after returning home from the hospital, and improve their ability to do the things they want to do. Lifestyle changes such as diet, exercise, stress management and improved sleep are all considerations.

As a rehabilitation researcher focusing on stroke prevention and management, Dr. Sakakibara knows how overwhelming these challenges can be and is exploring how technology can help to improve recovery.

“Depression and lack of activity are common after stroke, especially during in-patient rehabilitation,” he says. “Our latest project — in collaboration with Interior Health and the Kelowna General Hospital Foundation — is addressing these issues by examining the potential benefits of using virtual reality tools.”

Virtual reality (VR) platforms already have a large role in gaming and industrial settings, but they could also be an innovative and cost-effective therapy option for stroke patients. While studies have shown that VR can help improve physical and functional recovery, there is limited research on its effects on mood and patient activity levels.

This is where the games begin for Dr. Sakakibara and his team. Their research will examine the effect of interactive VR programs like games, activities or relaxation on mood and activity levels in stroke patients.

“If we can improve the mood of stroke patients during their in-hospital treatment, it may offer additional benefits to their recovery and lead to better clinical outcomes,” explains Dr. Sakakibara.

Delivering Care Online

The benefits of technology like virtual care, which deliver care without in-person physical contact, are also being explored by UBCO researchers. Both Dr. Sakakibara and nursing researcher Dr. Kathy Rush are interested in comparing the health impact of virtual care versus in-person delivery.

“Educational support is essential for people with chronic diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and those recovering from a stroke,” says Dr. Rush, a professor in the School of Nursing. Virtual care has been shown to be as effective — and sometimes more so — than in-person care for delivering education. This is an important healthcare option considering that 75 per cent of Canadians use the Internet to find health- and medical-related information which may not be reliable.

Both Dr. Rush and Dr. Sakakibara are assessing which platforms (telephone, computer or mobile device) make patients most comfortable and what type of information is most useful to them.

The technology needs to be relatively easy to use, and accessible by individuals while in their homes and communities, says Dr. Sakakibara.

“Although there might be some hesitation by current older adults using technology, the older adult of tomorrow will likely be very comfortable using technology,” he says. “This represents a large opportunity to develop and establish virtual models of care.”

Dr. Rush agrees with Dr. Sakakibara and even pivoted some of her research in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, polling patients and health-care providers living in rural BC communities about their technology use.

“I think I speak for everyone when I say my goal is to help those who’ve suffered from a stroke by allowing them to regain confidence in themselves and take hold of their future.”

“Surprisingly, the telephone was the most frequently used method of connecting,” she said, adding that this might have been the easiest and fastest way to adapt to virtual care during the pandemic.

For now, the telephone is the lowest common denominator, especially in rural communities where bandwidth is an issue. But Dr. Rush expects this to change over time, citing that many patients enjoy seeing their physician, even if they are seeing them digitally.

Regardless of the medium, it is becoming more likely that future health and rehabilitation consults will be virtual. In a recent study, Dr. Sakakibara found that virtual rehabilitation for stroke patients may be a more efficient means of delivering services and providing care options to those unable to attend conventional therapy delivered in-person. Although virtual services are not necessarily less costly, they can be provided to remote locations and accessed by patients in their homes. This is a critical advantage for those who live with physical disabilities following their stroke.

Monaghan is enthusiastic about the programs and services now available to support stroke patients when they return home. Almost a decade ago she had to climb the rehabilitation mountain with little help. She is a firm believer that the survivor has to participate in their own recovery. To help others, she advocates for improved services and outreach programs, and also volunteers her time to the cause.

“I think I speak for everyone when I say my goal is to help those who’ve suffered from a stroke by allowing them to regain confidence in themselves and take hold of their future.”

Similar to Dr. Wilson, she’s following her heart, embracing every beat.