AIRBORNE. AIRFLOW. DROPLET. AEROSOL. Since the arrival of COVID-19, these words have become commonplace, integrated into everyday conversations as quickly as the virus spread globally. But what remains unclear—and requires further study—is the role of airflow, droplets and aerosols in the transmission of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases.

That’s where a team of researchers from UBC Okanagan’s Airborne Disease Transmission (ADT) Cluster of Research Excellence come in. The group is dedicated to studying airborne diseases, with the overall goal of reducing the transmission of respiratory infections.

“What we’ve learned from the COVID-19 pandemic is how much we don’t understand about airborne disease transmission,” explains Dr. Sunny Li, research and development lead for the cluster and an associate professor in UBCO’s School of Engineering.

He points to the fact that people originally thought surfaces were the major transmission route for COVID-19, and then only later realized that it is mainly transmitted through the air. Dr. Li says airflow dynamics as well as the interaction between airflow and particles are complicated, and as a result the movement of particles is hard to predict. However, one aspect is certain; when it comes to understanding airborne transmission, size matters.

“Think about the dust particles you see dancing in the sunlight,” he suggests. “Because they’re large, they don’t move far and eventually fall to the ground. Viruses, however, are incredibly small and they can stay suspended in the air for a very long time, similar to how pollen stays in the air. They’ll travel with the flow of air and that’s how they spread disease.”

“If we better understand airborne disease transmission, we believe we can develop technology to reduce its spread and infection.”

At 0.1 micrometres (μm) in diameter the coronavirus is ten times smaller than a dust particle, which in turn is 10 times smaller than a white blood cell. Such particles with sub-micrometre diameters are referred to as aerosols, while larger liquid particles—which can carry smaller particles within them like viruses—are usually called droplets.

The lack of information about the spread and infectivity of these small particles spurred Dr. Li to bring together a team of researchers from UBC Okanagan and Vancouver, and the University of Toronto. With expertise in multiphase flows, computational fluid dynamics as well as health and technology innovation, the group have formed the ADT research cluster, an interdisciplinary network of researchers focused on solving key challenges facing society. Armed with new insights from experimental investigation, computer modelling, clinical trials and manufacturing, the research cluster hopes to scrub airborne disease from the air.

“If we better understand airborne disease transmission, we believe we can develop technology to reduce its spread and infection,” Dr. Li says.

“Our research needs to go beyond the lab and into real-world scenarios,” he adds. “Because some data is collected in a controlled environment, it may be misleading. We need both real-world and lab data because they complement each other.”

Dr. Li is working with ADT research cluster co-lead Dr. Jonathan Little from the School of Health and Exercise Sciences, along with Dr. Joshua Brinkerhoff from the School of Engineering to test experimental protocols in classrooms, hospital rooms and dentist offices. There are now some promising preliminary results.

Air scavenger for health and dental procedures

With the support of a Mitacs Accelerate grant, an early ADT cluster project tested an airborne infection isolation and removal (AIIR) device developed by CareHealth Meditech for use in dental offices. With a similar look to an old-fashioned hairdryer, the device was designed to isolate and eliminate airborne droplets generated during dental procedures.

“Many dental procedures generate aerosols, or small droplets that may contain infectious particles,” says Dr. Li. “The key to control transmission is to scavenge them locally before they circulate through the room.”

The initial lab experiment involved performing dental procedures on a mannequin connected to a breathing simulator. Fluorescent powder was applied to the mannequin’s teeth and mouth to track the spread of potentially infectious particles. Ultraviolet light was then used to visualize droplet and aerosol creation and dispersal, along with the dentist’s exposure to the simulated pathogen.

According to Dr. Li, early findings have shown that the AIIR device is effective at removing large droplets and aerosols. While it’s currently being used in some dentist offices, the cluster is exploring ways to improve the design.

“Our team is looking at the device’s size and geometry in connection with its airflow dynamics and the dynamics of droplets and particles to see if we can make units that are more accurate and efficient,” says Dr. Li.

Building on this experimental design, the next step of the ADT research cluster was to evaluate a scavenging hood in a health-care setting, in partnership with the Pritchard Simulation Centre team at Interior Health. Instead of sitting in a dental chair, the mannequin was placed on a hospital bed and exhaled glowing fluorescent particles while a tube was inserted into its airway. Researchers assessed the ability of an airflow dome to remove potentially infectious aerosols while the intubation was performed, and the ease of working around this new piece of equipment.

“So far our findings are encouraging,” says Dr. Little, the health lead of the ADT research cluster. “The dome device efficiently removed the tagged droplets and inhibited their spread. Now we’d like to see how it will work during different medical procedures and how comfortable the health-care team feels around it. Adding a new piece of equipment into an already crowded operatory or procedures room can be tricky.”

Dr. Jared Baylis, medical director of simulation for Interior Health and the UBC Southern Medical Program, is enthusiastic about this new simulation research and the opportunity to collaborate. “This is exactly what our program is designed to do. We’re well set up and have the practical expertise to run the experiments proposed by the ADT research cluster. We look forward to supporting more of their research.” He notes that this research and ongoing studies are made possible thanks to funding from the Colin & Lois Pritchard Foundation Student Enhancement Fund.

Dr. Little adds that although getting the right fit for these scenarios may take some time, “we need to figure this out,” so that life-changing procedures are not delayed by rising infection rates.

Back to school

The ADT research cluster is also evaluating potential infectious air transmission in classrooms. In this case, a mannequin is placed at a desk and exhales particles that are tagged with a marker that can be identified and counted. Initial studies compared the particle spread of a fully active heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system with one that was turned off. Once again, early results are encouraging.

“When the HVAC system is fully turned on, there’s better particle clearance in the classroom,” says UBCO alumnus and ADT research coordinator Jake Winkler. “This suggests that ventilation and filtration of the air can play a significant role in reducing airborne transmission of disease.”

Winkler points out that in this early experiment, there is just one simulated source of contamination in an empty room. Factors like multiple sources of infection, viral load, the number of people in a room as well as their movements and activities also need to be considered to develop a more complete picture of aerosol generation and how to reduce transmission.

Enter the world of computer modelling.

“The room itself impacts the transmission of air,” says Dr. Brinkerhoff, aerospace engineer, airflow expert, and indoor environment team lead for the cluster. “We saw this in the rapid spread of COVID-19 in long-term seniors’ care homes, where many residents were in one room and ventilation was not optimal.”

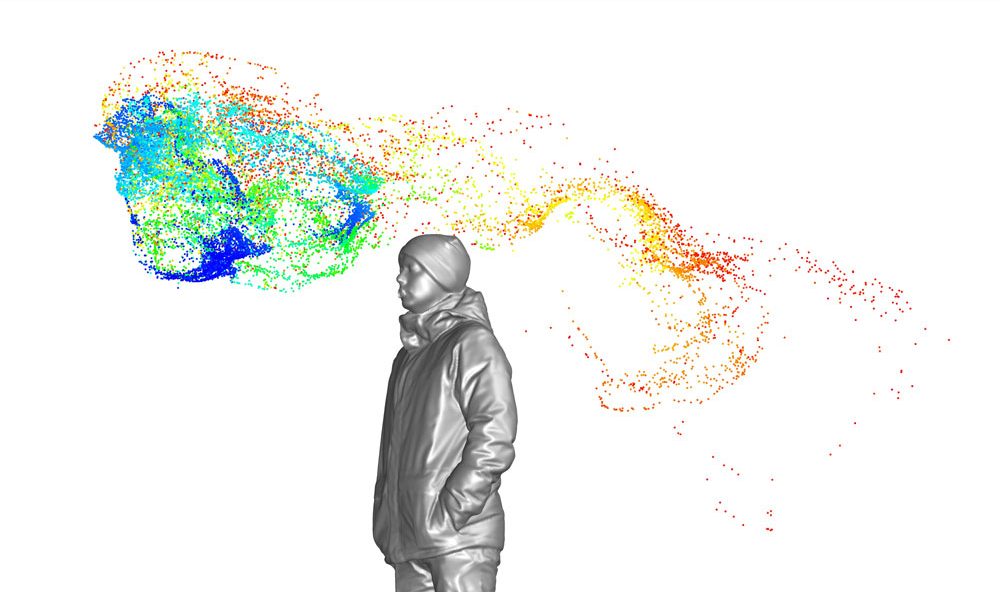

This numerical model developed at UBCO shows droplets and aerosols after a person has coughed in a room. The colour indicates how long the droplets and particles have been lingering in the air, with red being the longest.

Dr. Brinkerhoff’s team is using computational methods to investigate how indoor spaces, their ventilation and infection control systems, and the actions of occupants in these spaces impact the transport of air and airborne droplets and aerosols.

“We need to accurately simulate the fluid flow in time and space,” says Dr. Brinkerhoff. “To do this, we are constantly adding new inputs to our calculations, like data generated in the classroom and simulation centre.”

Dr. Brinkerhoff adds that the computational models can be adjusted to improve accuracy of predictions for certain scenarios. While he admits this is challenging research due to the diversity in rooms, people and environments, he’s optimistic about the power of computer simulations.

“The more data we collect, the better the prediction. We’ll be able to anticipate the outcome of having more than one infection source or increased room occupancy.”

He adds that the computing power required to perform these simulations is huge, requiring the equivalent of over 500 laptops running in parallel. He is thankful for the added brainpower of the UBC ARC Sockeye supercomputer, which Dr. Brinkerhoff connects to remotely.

Flowing into the future

COVID-19 and other aerosol-borne diseases are here to stay and the pandemic has highlighted that our understanding of how viruses spread in the air is inadequate. Determining how infectious particles move in the air and what strategies can be used to reduce infection will remain a major public health issue.

“The findings of our research will benefit everyone, from physicians to politicians,” says Dr. Little. “Removing infectious disease or contaminants from air will always be relevant.”

Dr. Li agrees and this is why his research and development team is focused on innovative devices that can locally isolate and purify infectious airflow. He anticipates that these will become as common as air conditioners.

Dr. Brinkerhoff goes a step further by suggesting that the ADT cluster will help guide the creation and operation of new air handling strategies in buildings. He predicts that approaches to reduce airborne infections will increasingly be incorporated into building design.

“I think we’ll soon see health outcomes become as important a factor as efficiency and cost in the design of new buildings.”

We can expect that these innovative health solutions will add new words to our ever-growing vocabulary around airborne disease transmission, while increasing public health.