Project

Preserving and Restoring Okanagan Syilx Plants and Endangered Regional Seeds

School

Okanagan School of Education

UBCO Contributors

Dr. Sumer Seiki

Joshua Smith

Becki Jaworski

Antreas Pogiatzis

SOME PEOPLE MAY HAVE LOOKED OUT AND SEEN A FIELD OF WEEDS, but Dr. Sumer Seiki saw an opportunity.

Dr. Seiki, an Associate Professor in the Okanagan School of Education, had an idea that would physically bring truth, reconciliation and healing into her classroom. In spring 2023, Dr. Seiki and 140 teacher candidates took on a massive project to transform an unused field area on campus into a rich biodiverse space for native plants.

“In BC, invasive weeds have taken over a lot of the grasslands, and it’s become a big problem,” says Dr. Seiki, who has a background in plant biology.

“According to Syilx knowledge, the land is a living entity intricately woven into their cultural practices, captikʷł stories, language and way of life. We are a part of a reciprocal relationship to the land; we give and it gives life to thrive.

“By learning about and practicing ecological restoration, we’re helping to make the land thrive again while also honouring Syilx knowledge.”

After removing the invasive species, candidates prepared the land by spreading compost to promote native seed development.

To assist with her project—called Preserving and Restoring Okanagan Syilx Plants and Endangered Regional Seeds—Dr. Seiki reached out to Xen Xeriscape Endemic Nursery & Ecological Solutions for advice on restoring the land.

“The Okanagan is incredibly unique; it has everything from an interior rainforest to the driest of the dry sagebrush slopes where almost nothing grows,” explains UBC Okanagan alumni Joshua Smith, manager at Xen. “We have native plant seeds at the nursery that need fire or need to be eaten in order to germinate.”

Xen works with local communities and developers on restoration projects to bring in native plants and re-establish the natural environment. To date, the organization has grown 120 different species of native plants and cultivates up to 70,000 plants annually.

“Native species are acclimatized to the arid area, meaning they can tolerate the high and low temperatures, and they don’t need as much watering,” says Smith. “Many household gardeners are changing to native plants because they’re tired of their hydrangeas dying or their cedars being eaten by deer.”

Besides the fields, candidates cleared weeds from the mindfulness circle and learning garden on campus.

Sulphur cinquefoil, an invasive weed.

After dividing up the 28,000 square feet of invasive weed land into field plots and dividing into teams, teacher candidates used the iNaturalist Seek app to map out the area and identify the different plant species.

Over the course of 10 days in April, candidates categorized the plants and dug deep to pull out the invasive weeds at the root level.

Finally, after laying down a layer of compost to aid in water absorption, they spread a mix of native seeds containing grasses and wildflowers that were crafted by Smith and campus sustainability.

Antreas Pogiatzis, a Bachelor of Education (BEd) student, is no stranger to working with soil. He previously worked at Xen, and both his undergraduate honours and master’s research involved mycorrhiza fungi, a symbiotic fungus that lives in the root of most plants and aids in nutrient uptake.

From left to right: Ben Robideau, Jeff Symonds, Annie Scollon, Kennedy Fletcher, Brianna Harrison and Julia Strother.

“I think the first step towards getting people to care about the land is helping them understand its importance,” says Pogiatzis.

“For some candidates, working on the land in this way was new to them, and the project was a tangible way to make connections; if you disturbed something on the land it could have a massive impact on other plants or animals.”

In addition to making connections with the land, the candidates were able to leave a lasting legacy.

“The work the candidates did in only 10 days made, and has continued to make, positive climate change gains,” says Dr. Seiki. “Over the course of a year, the native grassland plot and plants in the garden will capture about half a ton of carbon.

“Native plants have the added benefit of storing carbon in the soil because of their long, intricate root systems and their symbiotic relationships with fungi. It’s a significant contribution to our global health and reducing our carbon footprint.”

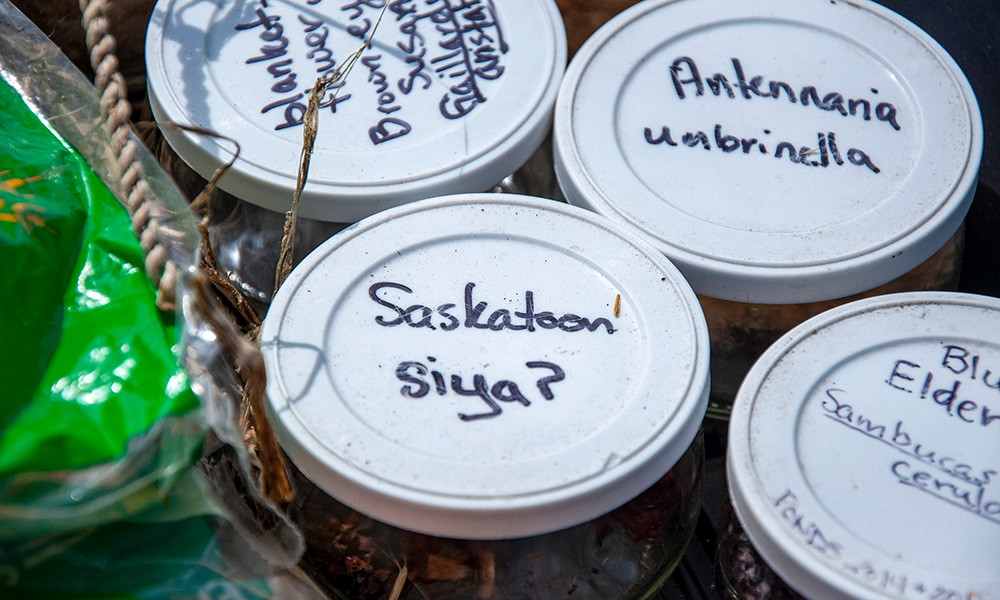

The seed collection of guest speaker Tanis Gieselman, a local ecological restorer. Gieselman collected local and native seeds and gave some to students after presenting to and working alongside them in the grasslands.

A lesson Gieselman shared on how to create a local garden in a school setting with students. Working with elders to develop this map, Gieselman shared with teacher candidates how the garden would change with each season and what to do with students during each timeframe.

In June, the candidates returned to their field plots again to weed out the invasive species and plant more native ones.

“It was a bit disheartening when we returned to the fields and saw that despite all our efforts to remove the invasive plants, the weeds were able to return,” says Becki Jaworski, another BEd student.

“For me, the project was a lesson in patience. It’s not about fixing everything really quickly. It’s the opportunity to do it right, and continuously work on it.

“This project gave us a chance to connect with the land. It disconnected me from the idea that I’m thankful for living on this land to being really thankful for being part of it—for being part of everything it provides us.”

In the spring, a new cohort of teacher candidates will return to the fields to continue the work of preserving and restoring the land. Dr. Seiki hopes to continue to grow the project and develop a seed library in the future.

Teacher candidates return to the now-lush field the following spring.

“While we were working, we were thinking about what is colonization, and what does it mean to decolonize?” says Dr. Seiki.

“I think sometimes these theoretical ideas can get lost in the moment of putting theory into practice, but social change, social justice and movement towards equity, require practice. That’s living out of theory into action. That’s what the candidates were doing; they were embodying the difficulty and the dedication needed to live out praxis.”

Through this restoration project, candidates were able to learn through doing, an important component of the BEd program. They learned how to teach and foster a connection with the land in ways that will help them promote environmental stewardship among their future students.

From this experience, Jaworski is looking forward to one day taking her own students out of the classroom.

“I want to have the children outside, getting their hands dirty and becoming experts of the land with the goal of passing that knowledge on to others,” she says.

“There are also opportunities for them to reflect and have wonderings, like who was on this land before, what would it have looked like before, what will it look like in the future?”

Pogiatzis echoes the sentiment.

“I’d like to help students understand how food grows, and how, for example, the soil can impact the quality,” he says. “Not every student has access to green space at home so I’m thinking of projects we can do at the schools, like starting a community garden or planting trees.”