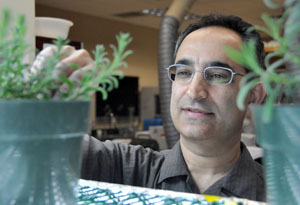

Biologist Dr. Soheil Mahmoud is studying the genetic content of lavender cells to better understand how the plant produces its valuable scented oils.

Innovative genetic detective work is underway at UBC Okanagan, where biologist Soheil Mahmoud and his team have received $78,000 from Genome British Columbia to explore some long-standing mysteries about how plants like English lavender produce their highly prized scented oils.

The project could one day have a big impact on B.C.’s lavender production by leading to the development of new varieties of lavender that produce essential oils in greater quantity or higher quality, says Mahmoud.

“We will be isolating and analyzing the expression of 10,000 genes as the lavender flower develops, so we can see which genes relate to the production of essential oils,” he says.

Mahmoud’s laboratory in UBC Okanagan’s Irving K. Barber School of Arts and Sciences studies the molecular, cellular, biochemical and environmental factors that regulate the quality and quantity of aromas and essential oils produced by herbal and medicinal plants. Using a microarray — an advanced-technology device with a special “gene chip” about 1 cm square — Mahmoud and his team will be able to study thousands of genes simultaneously.

In the past, the team has looked at genes from a random sampling of cells taken from the entire leaves and flowers of lavender plant, a study supported largely by the National Sciences Education Research Council, UBC Okanagan, the National Research Council’s Plant Biotechnology Institute in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, and the Investment Agriculture Foundation of B.C. Mahmoud says the next step is to target genes only from the oil-producing gland cells of the lavender flower petals.

“The Genome BC funding will allow us to isolate 10,000 genes specifically from these glands,” he says. “We’re increasing our odds tremendously — as fewer than one in every 1,000 cells is a gland cell.”

Knowing which genes govern essential oil production, or the production of undesirable compounds such as camphor, would help biotechnologists to develop agronomically improved varieties of lavender that produce oils more quickly, or that are more pure. Plant breeders could also use the genes as markers to detect varieties of lavender with desirable characteristics.

“Lavender is an important plant around the world,” says Mahmoud. “Each year, the world’s lavender growers produce about 2,000 to 3,000 tonnes of oil for use in a wide variety of products such as perfumes, colognes, shampoos, and for use in aroma therapy and alternative medicine.”

The Okanagan region — B.C.’s primary lavender-growing area — has a few dozen lavender farms, but most are small compared with large European producers with thousands of acres planted in lavender.

“Because the industry in the Okanagan is small, it has a niche market — it has to have very high quality oil,” says Mahmoud. “Both the oil and the aroma contain over 50 biochemical compounds and our quest is to understand how plants produce these compounds.”

— 30 —