People with eating disorders need to find healthful relationships with exercise

UBC researcher Danika Quesnel says telling people who are undergoing treatment for an eating disorder to completely abstain from exercise can be detrimental to the patient’s recovery and long-term health.

Quesnel’s research has determined that the traditional prescription to treat an eating disorder—encouraging people to refrain from exercise—may not be as effective as initially believed. In fact, it could be potentially detrimental to long-term prognosis.

Quesnel, who completed this research while an interdisciplinary student in UBC Okanagan’s School of Health and Exercise Sciences and the psychology department, says there is a definite disconnect when it comes to how much exercise should be allowed for people with an eating disorder. In fact, there is no simple “one size fits all” recommendation.

Quesnel interviewed a number of eating disorder health professionals throughout North America and Europe. She says it’s common for someone with an eating disorder to have a dysfunctional relationship with exercise.

“Dysfunctional exercise behaviour, meaning someone who has an abusive relationship with exercise, is present in around 30 to 80 per cent of patients with eating disorders,” says Quesnel. “However, the exercise behaviours are not commonly addressed when that person is being treated for an eating disorder. In fact, people are often told to stop exercising. Period.”

While it is hard to monitor and ensure that a patient is not engaging in inappropriate exercise when they have been recommended not to, Quesnel says it’s more complicated than that.

“It’s not a realistic option. Both clinical and research experts can agree on that,” she says. “What we should be doing is developing guidelines to incorporate healthy amounts of exercise into the treatment so we can help patients develop long-term, appropriate relationships with exercise.”

Ideally, Quesnel says a person being treated for an eating disorder, should be encouraged to take a break in the activity they are they overdoing. For example, someone who compulsively runs could eventually be encouraged to try a different activity or a team sport.

“It’s an emerging topic, one that is on the minds of many, yet little information is available,” she says. “How much is the right amount? There needs to be a gradual protocol that begins in treatment and needs to be based on the patient’s physical health, activity goals and preference. The ultimate goal is that they develop a healthy lifestyle around physical activity beyond the context of treatment.”

It’s also important, she says, to tailor the activity to each individual and introduce flexibility, strength training and then cardiovascular exercises in stages which a patient progresses through based on their health.

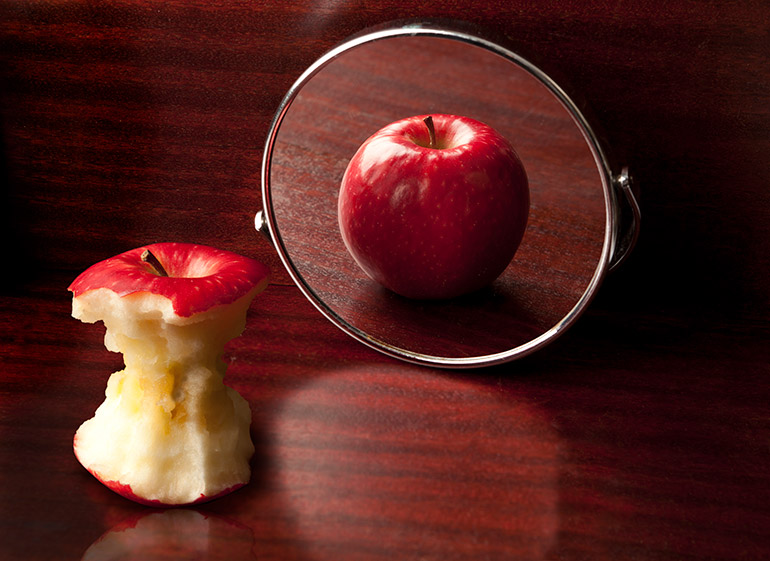

“Exercise prescription can be tricky in the context of eating disorder treatment,” she says. “These are people who have very dysfunctional relationships with exercise. We need to help patients develop a healthy relationship with exercise, just as we help them improve their relationships with food. We need to be able to give them an exercise program that matches with their treatment goals and one they can follow for the long term.”

Quesnel’s research was published recently in Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment and Prevention.