Location

Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre

Course

In Pursuit of the Whale

Faculty

Creative and Critical Studies

Professor

Greg Garrard, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies and Research & Associate Professor of Sustainability

HUMANITIES STUDENTS, UNLIKE THOSE IN SCIENCE PROGRAMS, ARE SELDOM SEEN GAZING INTO TIDE POOLS along the shores of the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre on the remote west coast of Vancouver Island. UBC Okanagan Assoc. Prof. Greg Garrard intends to change that.

Garrard is the tidal force behind the environmental literature course In Pursuit of the Whale, where students examine works relating to whales and whaling. It’s the first-ever literature field course taught at the marine sciences centre.

The Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre (BMSC) was established in 1972 as a field lab for those studying marine biology. Visiting the isolated centre — owned by the Universities of British Columbia, Victoria, Alberta, Calgary, and Simon Fraser University — has become a rite-of-passage for West Coast students of marine science. But for literature students, leaving the hallowed halls of learning for the coastal environs of Bamfield is a unique proposition.

Garrard’s attraction to create a course at a research facility dedicated to the natural sciences was two-fold.

His research and teaching are in the fields of environmental literature, ecocriticism and human-animal relations, and he’s an advocate for interdisciplinary learning.

Aside from the ideal setting — “the watery part of the world”, as depicted in Melville’s tome Moby Dick — Bamfield is also part of Garrard’s family history. The centre is built on top of an old cable station where Garrard’s grandfather received and sent telegrams during the Second World War.

“My grandad worked at the cable station in Bamfield and my father grew up there in the 1940s. It just fascinated me that there was this place that was so significant to my family that I’d never been to.

“I contacted them and asked: ‘How would you like to host a course in whaling literature?’”

As a result, In Pursuit of the Whale was first offered in Bamfield in summer 2016. A second instalment of the field course wrapped up in July 2018.

During the three-week intensive course, graduate and upper-level undergraduate students dive into not only Moby Dick, but Phillip Hoare’s The Whale, Australian Aboriginal writer Kim Scott’s That Deadman Dance and Farley Mowat’s A Whale for the Killing.

“What could be more ideal than to read Moby Dick at the site of an abandoned whaling village?” asks Garrard.

Students visit Kiixin, an abandoned whaling village not far from the marine science centre, and hear stories from a Huu-Aye-Aht guide. “Both times we taught the course a village elder showed us the whaling Chieftain’s longhouse, abandoned over a hundred years ago, and pulled bones out of the undergrowth, grey whale bones.

“It’s gone really, really well,” says Garrard. “We want students to think about what it means to read literature in a particular place, and Bamfield is an extraordinary place in terms of human-whale interactions.”

The remote locale also provides a unique learning experience. To get to Bamfield, students must either take a float plane, a boat, or a very long and rugged logging road.

“There’s not much phone reception. The Wi-Fi is terrible. There’s nothing to do really except read, talk to other students and experience the place. And that’s extremely unusual for young people today,” adds Garrard. “I don’t say that with any rancor or anything. I think it’s just hard for them to disconnect. In Bamfield you have to disconnect.”

While the scientists at the BMSC are at first puzzled by the presence of the literature students, Garrard says both students and researchers quickly recognize the value of interdisciplinary work.

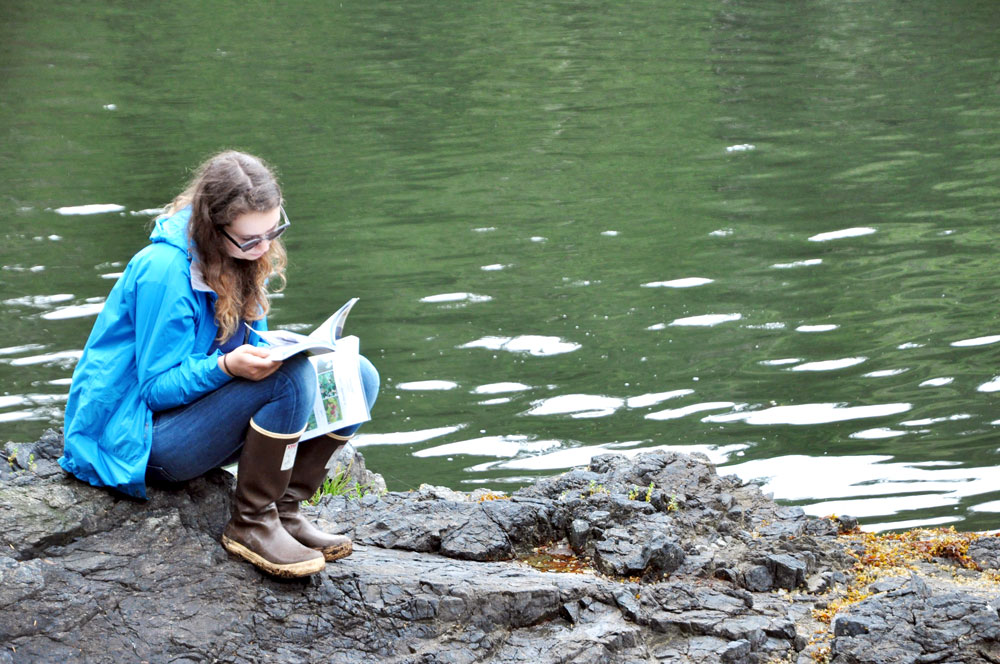

“The science students are out there in scuba gear. Our students are on the beach contemplating and reading. They spend their time completely enveloped in this kind of real and fictional world.”

Amidst whale watching expeditions, marine life studies, and rainforest hikes, the literature students write papers working closely with Garrard, teaching assistants and other students studying marine science.

“Because we’re all living there, we are able to sit down with students in person and spend a lot of time on their writing.

“We also have the opportunity to engage on a deep level with what science students and marine scientists do there. It really is a very powerful kind of interdisciplinarity,” explains Garrard.

Learning in the field enables students to examine the interplay between the physical and cultural environments, says Garrard. This works well with the overarching theme he imbues into all of his teaching.

“The distinction between nature and culture is artificial…it is itself a cultural distinction. It is in human nature to be cultural and it is in the nature of human culture to change the places that it inhabits. The nature-culture feedback, I call it.” Garrard pauses here and adds with a chuckle: “And that’s really all I ever really talk about.”

In Pursuit of the Whale aims to challenge and reshape students’ views on the environment and the culture of whaling.

Garrard says students generally arrive at the course with a bias for whale conservation. The course often disrupts these established views.

During the most recent offering, Garrard proposed this question: Who do you think is the world’s leading whaling nation today in terms of the number of whales killed?

“Of course students were like, ‘Well, I guess that’s Japan or Norway or Iceland’. And it’s not. It’s Canada — by some way actually,” says Garrard. “That’s because of Indigenous whaling in the North. Canada isn’t a member of the International Whaling Commission. It left a long time ago. It regulates its own whaling.”

While being exposed to Indigenous perspectives often shifts students’ views on whaling, the course also asks students to question their ideas on whale watching.

Students in Pursuit of the Whale spot a pod of killer whales off the shores of the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre. “We came across what the marine biologists have named k-pod. They were teaching their young to fish. The skipper of our boat said he’s never seen anything like it in his 30 years on the West Coast.”

“It may seem like a harmless activity, but then when you ask yourself…‘Why are you doing this and what’s the impact of this?’…then some of those questions can be uncomfortable.”

Garrard says his students are often profoundly impacted by witnessing whales in the wild. He believes this comes back, of course, to his theory of the nature-culture feedback.

“We are all aware of the horrors commercial whaling visited on whales. Many of us feel a sense of guilt, not necessarily about whales, per se, but about the environment and our relationships with animals,” he explains.

“So, to encounter them and experience their presence actually feels like a kind of forgiveness.”

While most populations of whales will never be fully returned to pre-19th century numbers, many are making a comeback, says Garrard.

If Garrard has a bias, he says it’s probably towards optimism.

Ideally, Garrard says he would like all the students to be environmentalists, but that’s not his intention or what his work is about.

“I don’t necessarily think that it’s my job to make them environmentalists if they’re not already. Because this is a university, our job is understanding. And where that understanding may take you is not in my control.”

Garrard will to continue to teach In Pursuit of the Whale at the BMSC every two years with his colleague, Assoc. Prof. Nick Bradley from the University of Victoria. The next course is planned for the summer of 2020.

—Written by Craig Carpenter