CANADA’S POPULATION IS AGING — by 2036, it’s estimated that adults over the age of 65 will represent more than 20 per cent of the population. And this growing demographic craves autonomy and a fulfilling quality of life enriched by community.

From this lens of being informed by older adults, researchers at UBC Okanagan (UBCO) are examining how to best support the goals of our aging population to help them age successfully and with satisfaction.

For many, adapting to the unique pace of being an older adult isn’t easy. Add retirement, a potential empty nest, declining health, and the passing of a loved one or spouse, and many aging adults are left struggling with a new reality.

“Significant life changes happen after the age of 50 that can trigger mental health concerns,” says researcher Nelly Oelke, an associate professor at UBC Okanagan’s School of Nursing. “Typically, we don’t think about overall mental health in older adults and instead concentrate mainly on their cognitive abilities.”

She suggests this is an oversight.

“One in five individuals will have a mental health concern during their lifetime. This doesn’t go away as people age.”

“One in five individuals will have a mental health concern during their lifetime,” says Oelke. “This doesn’t go away as people age.”

She adds that high rates of suicide are found in men between the ages of 45 and 65, but startlingly, the highest rate occurs in men over 85 years of age.

“These are our brothers, parents and grandparents,” says Oelke, who adds that social isolation, which happens often as we age, is a huge contributor to depression.

“Men are more likely to experience this than women — traditionally they have fewer relationships with less depth of intimacy. In addition, many older adults live in rural communities, which may limit their social networks.”

Oelke and others from UBCO’s Institute for Healthy Living and Chronic Disease Prevention (IHLCDP) research team are exploring how to reach these individuals, assess their needs and implement programs to bring them back from the brink of loneliness to a caring community.

The team’s first step was to reach out and see what services would be helpful.

With supervision from Oelke, Masters of Social Work student Ian Pryzdial sought to better understand the health status and wellbeing of men living in southern Okanagan rural communities.

“In this study we were focusing on all men 19 and over, but interestingly, participants were all 50 and over,” says Oelke. She says this isn’t particularly unusual, since half the population in these communities is over 50.

Pryzdial tried to connect with the rural group but unfortunately, “Men shy away from conversations,” he said. “Especially in a formal setting.”

Masters of Social Work student Ian Pryzdial with a member of the Men’s Shed.

So the researchers decided to change their approach. UBCO partnered with the Okanagan Men’s Shed Association (OKMSA), a non-profit society with a mandate to engage men of all ages, foster social connections and increase their wellbeing and self-esteem through participation in community projects.

The Men’s Shed is where men (and recently women) enjoy building wood working items like bird and bat houses, benches, trays and vendors’ booths. But more importantly, shed members also connect with community organizations like Scouts Canada to teach children building skills.

“Men are more likely to experience [social isolation] than women — traditionally they have fewer relationships with less depth of intimacy.”

“We need to go where the men are,” agrees Joan Bottorff, UBCO nursing professor and director of the IHLCDP. Bottorff, whose husband coincidentally is an active member of the Men’s Shed, was instrumental in helping secure funding to support wellness and research initiatives there.

She explains that when men are brought together in an environment they’re comfortable in, they will often share their challenges and are more open to learning about their health.

Seeking Men

Decio D’Ornellas has warm brown eyes, an engaging smile and an infectious laugh. Originally an accountant, he now helps balance the books for the Men’s Shed.

“I have two left hands, so they keep me off the bandsaw,” says the ‘70-something’ year old. “The shed is somewhere I go every day. My wife passed away, my children live abroad and I was retired. I had nothing to do, and now I have purpose.”

D’Ornellas has a positive attitude, which can be hard for many older adults to embrace as they transition from their busy work and social lives to a quieter lifestyle. He’s enthusiastic about upcoming projects and enjoys the camaraderie of this space.

Pryzdial has witnessed the instrumental bonding that goes on amongst the sounds of hammers and drills. Here, friendships have blossomed and a caring community has been built, where everyone keeps an eye on each other.

This has continued through COVID-19 restrictions, according to Okanagan Men’s Shed president, Art Post. Although fewer members are allowed to be at the site at one time, due to physical distancing recommendations, they are still keeping busy.

“We took on a large building project during the summer, which was completed mostly outdoors,” Post proudly says, confirming the value of this organization and the commitment of its participants.

“Men’s social networks have traditionally been centred around work,” says Pryzdial. “Although they’re building items in the shed — or outside — they’re also establishing social ties.”

On the Road

The success of the Okanagan Men’s Shed and others around the country has led to a mobile shed initiative.

In partnership with UBCO, OKMSA built a stylized trailer with pullout cabinets that travels throughout the Okanagan, aiming to reach rural citizens. Pryzdial believes raising rural men’s awareness of Men’s Shed and its philosophy will be valuable.

“Our work and that of others illustrates that the aging population benefits from these types of outreach programs. Consistent social appointments and interactions will go a long way to help keep these individuals mentally, physical and emotionally fit.”

“We’re hopeful that rather than treating a mental health issue, we’re encouraging a proactive social environment,” says Oelke. “We’re letting them know: it’s ok to be ‘not’ ok.”

Happiest at Home

Older adults living on their own may be worrisome to the community, especially when they appear vulnerable, isolated or in declining health. Their safety, independence and overall wellbeing might need additional support services.

Barbara Pesut

That’s where Barb Pesut comes in. The School of Nursing professor and Canada Research Chair in Health, Ethics and Diversity (2010-2020) helped develop Nav-CARE, a service that helps support those with quality of life issues.

Whether it’s connecting these adults with community resources or helping them stay engaged, the goal is to improve their quality of life at home.

“Many older adults prefer to stay in their community and in their homes,” says Pesut. “As a society, we’d like to be able have their backs, literally.”

She adds that this growing and vital community deserves the dignity of independence and often thrives when they stay in their own homes.

Pesut and fellow researcher Wendy Duggleby from the University of Alberta proposed the innovative solution of connecting older adults with trained volunteers who can assist with daily non-health related functions, such as identifying resources in the community and providing emotional support and companionship.

Like a helpful neighbour or friend, Nav-CARE volunteers visit older adults in their homes on a regular basis, with a focus on enhancing their quality of life.

The research team evaluated the feasibility, acceptability and impact of this program across Canada for two years, and the results were encouraging.

“We were overwhelmed with the satisfaction and importance of the program from both volunteers and older adults,” says School of Nursing graduate student Paxton Bruce, who helped coordinate the project. “It was mutually beneficial; the volunteers gained experience, purpose and friendship and the older persons appreciated the help of someone knowledgeable.”

Bruce also noted that some of the clients were more likely to share their worries and concerns with a volunteer than a family member.

“The volunteer is unique: they’re neither paid nor family,” she says. “This shifts the relationship and creates a genuine interaction.”

Bruce says the program has been fabulous to coordinate. “Everyone wants to support their community and it’s been empowering to be part of this.”

Pesut agrees that encouraging a compassionate community has been fulfilling. “It’s wonderful to foster such pride.”

However, the recent emergence of COVD-19 has changed some of the dynamics. Now, instead of visiting houses, Nav-CARE volunteers are reaching out via phone or computer.

Pesut, along with Bruce, has started a new research project to gauge how the system is now working. She says that many seniors are coping well on their own and benefitting from some of the COVID-19 resources, such as online grocery shopping and virtual physician visits.

But Bruce adds that both volunteers and clients miss the in-person get-togethers. “Although everyone is grateful to be healthy, many agree it’s hard to have meaningful conversations on the phone,” she explains.

Pesut and Bruce hope to have a better understanding of what is working and how to improve what isn’t during the trying times of physical distancing.

The Physical Decline

The physical decline that accompanies aging is a reality few want to acknowledge.

UBCO School of Health and Exercise Sciences professor Jennifer Jakobi admits that not enough is known about how and why muscle abilities decline with age.

“The ultimate goal of our research program is to enable adults to live and function longer in the space they want to be,” she says. “We want to better understand the age-related changes that happen; specifically, between the spinal cord and muscle communication.”

Jakobi notes that physical decline as we age is unavoidable and happens earlier in women than in men.

“I want to use the information we gather to design exercise interventions to help mitigate this change. We need to help support individuals achieve their physical goals, whether it’s playing with grandchildren or running the next race.”

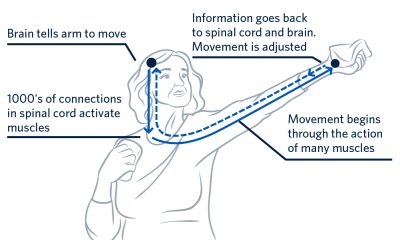

She explains that as we age, signals between the brain, spinal cord and muscles slow and might get confused. Jakobi’s Neuromuscular – Healthy Exercise and Aging Lab (HEAL) is one of only a few in the world to study the millions of messages relayed between the spinal cord and muscles, and how these interact with tendons for controlled functional movement.

“It’s a balance of positive signals telling the muscle that connects to the tendon to move, and then negative ones that stop the motion.”

While it’s amazing that this process works at all, it also shouldn’t be much of a surprise that it falters as we age.

“Part of aging is physical decline. This is normal,” says Jakobi. “Strength, balance and endurance just naturally wane.”

She adds that it’s the curiosity about this process and the people behind the studies who drew her into this type of work.

“Older adults are passionate about their lives and they want to keep moving. I’m right there beside them.”

Staying On Your Feet

Keeping on your feet is easy for most young people, but falls become common and deadly as people age. For an older adult, a fall may lead to serious injuries including broken bones and head trauma. Once a severe fall occurs, the fear of more stumbles can negatively impact an aging adult’s quality of life.

“Fall-related injuries are pricey; they can cost the health care system up to $30,000 per fall,” says Jennifer Davis, an assistant professor in UBCO’s Faculty of Management Social & Economic Change Laboratory.

“Expenses add up quickly and can include hospital admissions, fracture repair and subsequent treatments. Sometimes these injuries result in more serious conditions or even death.”

Davis has been researching the effectiveness and ‘value for money’ of fall prevention programs for more than 10 years and works as the co-director of research operations at the Falls Prevention Clinic. The organization is supported by local health authorities in the Lower Mainland and Northern Interior, and is run out of Vancouver General Hospital.

It’s in these clinics where health care teams tailor individual strategies for each patient. First, they assess the mobility, cognitive (mental) functioning and quality of life of individuals, followed by recommendations to minimize the risk of further stumbles.

Their strategy, centred around a geriatrician-based multidisciplinary approach, includes individually-tailored recommendations such as exercise prescriptions, medication adjustments and lifestyle modifications. And it’s been having a large impact.

“We’ve shown that we can prevent falls by up to 40 per cent, thereby reducing the burden on the individual and the health care system,” adds Davis.

She also notes that this process has other benefits beyond reducing fall-risk. For example, sleep quality is often an issue with older adults, and those who are prescribed sedatives for better sleep may be more likely to stumble at night when under the effects of prescriptions.

“Lack of good sleep and falls go hand-in-hand,’ says Davis. “This can lead to a downward injury-sleep disturbance spiral.”

She suggests that reducing sleep medication may not only result in a decreased chance of falling, but may improve sleep quality and mood as well.

“Unfortunately, we don’t have a pill that prevents a fall but a comprehensive approach looking at lifestyle interventions such as exercise and diet may decrease accidents and the burden on the healthcare system.”

Davis — like Oelke, Bottorff, Pesut and Jakobi — was drawn to this research because she sees a vulnerable population where her work can have a significant impact.

“Our research findings can help our aging adult population add quality years to their later life. I’m motivated to find effective and efficient solutions to make their future bright.”

The unifying theme of all these researchers is a desire to support individuals in their goal to age well in their space, on their terms and on their time. As American feminist Betty Freidan once said, “aging is not lost youth, but a new stage of opportunity and strength.”

And it’s this perspective — along with valuable research taking place — that older adults are likely to encourage, endorse and ultimately apply as they endeavour to age successfully.