IMAGINE BEING OUT IN PUBLIC AND SUDDENLY HAVING A PRESSING URGE to find the closest toilet. Immediately. Although this may not be unusual for the average person, when this symptom repeats frequently throughout the day and is accompanied by abdominal pain, bleeding, weight loss and fatigue, it can be debilitating. Unfortunately, this is a reality for the 270,000 Canadians currently living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

For UBC Okanagan microbiologist Dr. Deanna Gibson these numbers are unacceptable. Her research team at the Centre for Microbiome and Inflammatory Disease Research is focused on understanding the causes of IBD and other chronic inflammatory gut conditions, with the ultimate goal of developing treatments to ease patients’ suffering.

“IBD typically hits young adults and very often has a significant negative impact on their quality of life,” says Dr. Gibson, an associate professor in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science. “So, we’re trying to figure out what happens before their symptoms occur—when the story began, so to speak—and how we can influence that narrative.”

IBD BY THE NUMBERS

Number of people worldwide affected by IBD

Percentage of patients with symptoms mostly in their gastrointestinal tract

Average number of surgeries had by IBD patients

Source: worldibdday.org

Dr. Gibson and her team have the unique perspective that tummy troubles begin in infancy and are centred around the trillions of micro-organisms living in our intestines.

Known as the microbiome, this quasi-community includes a complex and diverse environment of bacteria that is essential for biological functions such as digestion and immunity. While microbiota normally live in harmony with their host, when they are disrupted a microbial war-of-sorts with the immune system results, ultimately forcing patients to take refuge in the bathroom.

“A healthy gut happens when a particular collection of microbes live symbiotically and are able to prime the immune system properly,” says Dr. Gibson. She adds that the difference between a healthy gut and a dysfunctional one comes down to which bacteria are dominant at any given time. Fortunately, her studies suggest that a change in diet or other environmental influences can establish a new regime.

Dictating through diet

During her two decades spent as a dietitian, Natasha Haskey was stumped on how to help individuals struggling with IBD. Frustrated by the lack of information about dietary triggers and causes, and motivated by the expanding demand from patients for help, she decided to find the answers herself.

Now a doctoral student with Dr. Gibson’s research team, Haskey decided to focus on the impact of a Mediterranean Diet on gut inflammation, one of the telltale signs of IBD. Inspired by the diets of Spain, Italy and Greece, the Mediterranean diet emphasizes ingredients like olive oil, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, as well as moderate to high consumption of fish.

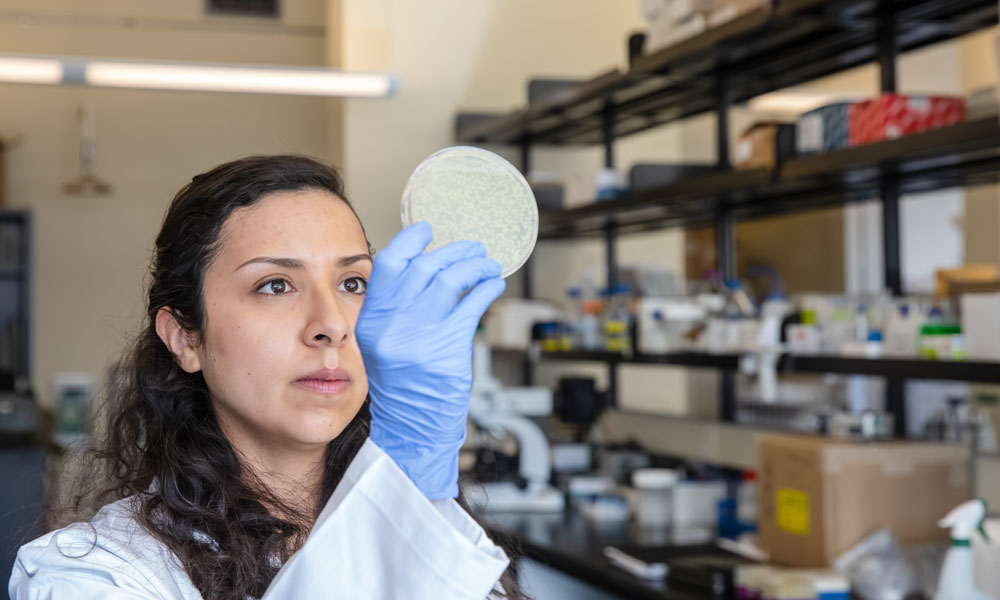

Doctoral student Natasha Haskey is studying the impact of diet on gut health.

“Previous research has suggested this diet is beneficial in conditions like heart disease and diabetes,” says Haskey, who notes that the diet’s focus on plant-based foods and healthy fats like olive oil mean it’s often touted as anti-inflammatory. “We wanted to know if this was also the case for IBD.”

Their study involved placing individuals with IBD into groups that followed the diet and those who didn’t. Researchers found that the participants who followed the Mediterranean diet had fewer IBD-related symptoms than those who didn’t change their eating behaviour.

In addition, researchers discovered higher levels of a bacteria-produced molecule called butyrate in those following the diet. “High levels of butyrate indicate a healthy gut,” explains Haskey. “Gut bacteria transform dietary plant fibre into butyrate, which in turn nourishes the gut’s cells. This helps support digestive health and also controls gut inflammation.

“We suggest that the increased fibre consumed through the Mediterranean Diet is associated with increased butyrate levels and leads to a happier gut of the participants.”

Fish oil: favourable or just fishy?

There’s been a lot of hype about the benefits of fish oil for babies, with claims that it has brain boosting and immune-enhancing properties.

This has led some breastfeeding mothers to take fish oil supplements in an effort to pass it on to their babies via their milk.

Dr. Gibson’s lab investigated whether these claims ring true or not.

“It’s amazing that 66 per cent of women in the Okanagan Valley self-administer fish oil supplements during their pregnancy,” says Dr. Gibson, who started examining fish oil in 2010. “Yet, there hasn’t been a lot of research showing its potential in supporting infant health, and its effect on gut microbiology is relatively unknown.”

Alumna Candice Quin joined Dr. Gibson’s fish oil investigation team as a doctoral student because she had a personal interest in the area.

“I saw that fish oil was being added to infant formula and being advertised as having really great effects,” explains Dr. Quin, whose sister was pregnant when she began her studies. “When my sister asked me about fish oil supplements, my interest in studying this further was piqued.”

For the study, Dr. Gibson and the research team evaluated 91 women and their babies; half took daily doses of fish oil while the other half did not. Breast milk, infant stool samples and immune function markers were then compared between the two groups.

Although women who took supplements had a higher ratio of omega-3 fatty acids, they had lower protective molecules like antibodies in their breast milk. The supplemented infants also had a lower diversity of bacteria in their stools, something that is considered negative.

“We showed that supplementing with fish oil decreases the critically-important defence factors of breast milk, which is one of the only sources of immunity infants get during early life,” says Dr. Quin. “We also showed that increased fatty acids in breast milk as a result of supplementation was associated with an altered composition of infant gut bacteria, both in numbers and diversity.

“This is a change that could result in infection risk for the infant,” she warns.

Like Dr. Quin’s sister, many parents are making every effort to ensure their babies are healthy. Reliable scientific data is critically important when it comes to helping these parents make the best decisions for their children.

LEARN MORE ABOUT

The gut and glyphosate

Interesting collaborations can materialize when researchers share labs, hallways and even lunchrooms. Take a casual conversation between Dr. Gibson and plant microbiologist Dr. Miranda Hart, which blossomed into a full-blown research priority for the Gibson lab.

Dr. Hart, also a professor in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science, knew that North America is one of the only countries to widely use the herbicide glyphosate in agriculture, and questioned if this could impact gut biology. Dr. Gibson decided to explore this idea with doctoral student Jacqueline Barnett, even though the findings could be controversial.

“We know that glyphosate isn’t toxic to the human body, but we’re not sure of its effect on gut bacteria,” explains Barnett.

The research team used an animal model of IBD, which specifically mimics symptoms of colitis, to test the effect of different doses of glyphosate on gut irritability, with some intriguing preliminary results.

“The animals who were fed either a low and high dose of glyphosate had an earlier onset of inflammation, indicating a disturbed microbiome,” says Barnett. “Defining the change in type or number of bacteria are the next steps.”

Barnett has also begun studying the impact of adding glyphosate to the diet of healthy animals. Her research has shown that animals who consume glyphosate undergo a behaviour change and become more anxious, ultimately passing this anxiety down through generations of offspring. She suggests this surprising effect occurs as a result of the glyphosate changing the type of gut bacteria, which in turn produces byproducts that reach the brain.

“We already know there’s a gut-brain interaction, and now our studies are showing how diet influences this,” says Barnett. “This area of research—looking at the interconnection between the environment, gut microbiology and disease—is exploding and we’re at the forefront.”

Disabling dysbiosis

Understanding the influencers of IBD or any other chronic gut condition is all fine and well, but relating this to disease treatment involves another trip into the bowels. This time, Dr. Gibson and doctoral student Andrea Verdugo Meza are using live biotherapeutic products, or beneficial bacteria that have been bioengineered, to treat IBD patients.

Although the concept is the same as probiotics—taking supplements to populate the gut with healthy bacteria—the Gibson lab’s biotherapeutics may have a better success rate.

“Often commercially available probiotics do not last long in the intestine,” says Dr. Gibson who anticipates their bioengineered microbes will survive and persist in the IBD gut. Currently, they are testing this.

Doctoral student Andrea Verdugo Meza is exploring designer probiotics.

“Gut disruptions, or dysbiosis, are miserable and debilitating, and usually involve the invasion of harmful bacteria,” says Dr. Gibson. “The idea of replacing these pathogens with beneficial bacteria seems like a simple solution, but timing and context is everything.”

She explains that gut microbiology changes with age and it’s important to acknowledge that there isn’t a “one-size-fits-all” option. Verdugo Meza adds that although there are many probiotics currently available, there are a lot of varieties and the experiences of taking them aren’t the same from person to person.

“The gut environment is unique and may support or inhibit newly introduced organisms. Also, if the new organism is able to colonize, it may not thrive.”

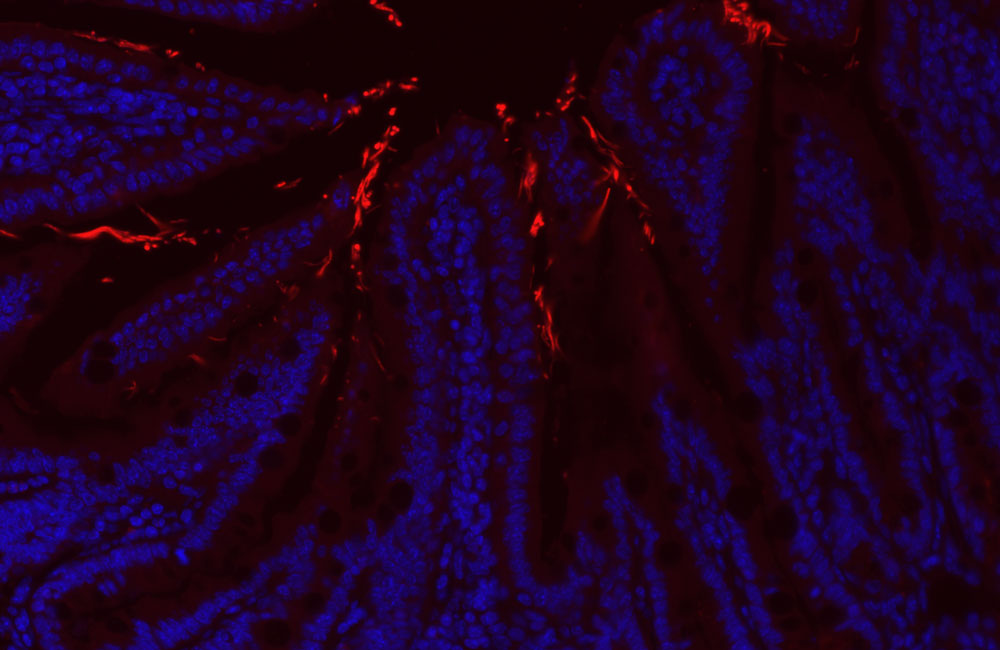

Taking this into consideration, the research team has developed innovative and tailored probiotics designed to improve this colonization and persistence. They tested the effect of these in an animal model of IBD and early results have been promising.

“The animals that received the live biotherapeutic products had decreased IBD symptoms compared to those who received the non-engineered probiotic,” says Verdugo Meza. “We now need to follow up to see what’s happening to the microbiome.”

Dr. Gibson is optimistic that this may be the first step to helping those with IBD. She is in the process of finding a commercially viable path forward and building a UBC spin-off company to further develop this innovative targeted therapy for IBD patients.

Her ultimate goal is to have a solution for people with IBD or other chronic gut conditions that can be delivered before inflammation, discomfort and distress begins.

“This disease shouldn’t be a never-ending story. I’m hopeful our work will improve the lives of those suffering from IBD and bring an end to this particular trauma for them.”