FOR MOST PEOPLE, PLUNGING INTO AN ICE BATH and shivering for 30 minutes in front of a classroom full of students doesn’t sound like much fun. But for undergraduate student and ice bath volunteer Justin Monteleone, it’s all in a day’s work as a research participant in Dr. Phil Ainslie’s laboratory.

“I became interested in research after taking an Exercise Laboratory Techniques course last year and touring a professor’s lab,” explains Monteleone, who is studying for his Bachelor of Health and Exercise Sciences.

“I just had a sheer curiosity about what happens in these labs and why, so I began volunteering. Since then, I’ve had the opportunity to participate in a number of Dr. Ainslie’s studies and witness first-hand what world-class physiological research looks like.

“I wanted to share this experience with my class, so when Dr. Ainslie asked his fourth-year Environmental Physiology course if anyone would volunteer to demonstrate cold stress, I didn’t hesitate.”

The ice bath is a simple but practical illustration of some of the more significant themes of human physiology Dr. Ainslie explores in his lab, including key questions related to oxygen availability, exercise and adaptation in the body.

Dr. Phil Ainslie watches on as undergraduate student Justin Monteleone completes a hypothermia protocol. This involved laying submerged for up to an hour in seven-degree Celsius water.

As one of the first faculty members at UBCO’s School of Health and Exercise Sciences, Dr. Ainslie is a leading global researcher into how environmental stress affects the human body’s performance and survival.

Specifically, he aims to understand how the body copes with a lack of oxygen and extreme temperatures. He studies hypoxia (low oxygen levels in body tissues) in both healthy volunteers and elite athletes who train at the edge of human endurance.

He also researches individuals who experience a lack of oxygen to their tissues from an event like a heart attack or stroke, all to understand how the body—in particular, the brain—adapts in different ways to various stressors.

In the case of the ice bath, the class explored Monteleone’s response to the water temperature.

“The undergraduate students typically appreciate seeing that demonstration because it makes them think practically about what would happen if they suddenly fell into cold water and the physiological consequences of this stress,” says Dr. Ainslie, a Professor of Health and Exercise Sciences and Co-Director of UBCO’s Centre for Heart, Lung & Vascular Health.

“They were able to see Justin shiver, which helps the body produce heat to a certain extent. But when the shivering stops then body temperature plummets quite quickly, and the individual can perish soon after that. Motor function is lost almost immediately, highlighting why drowning can occur even in strong swimmers.”

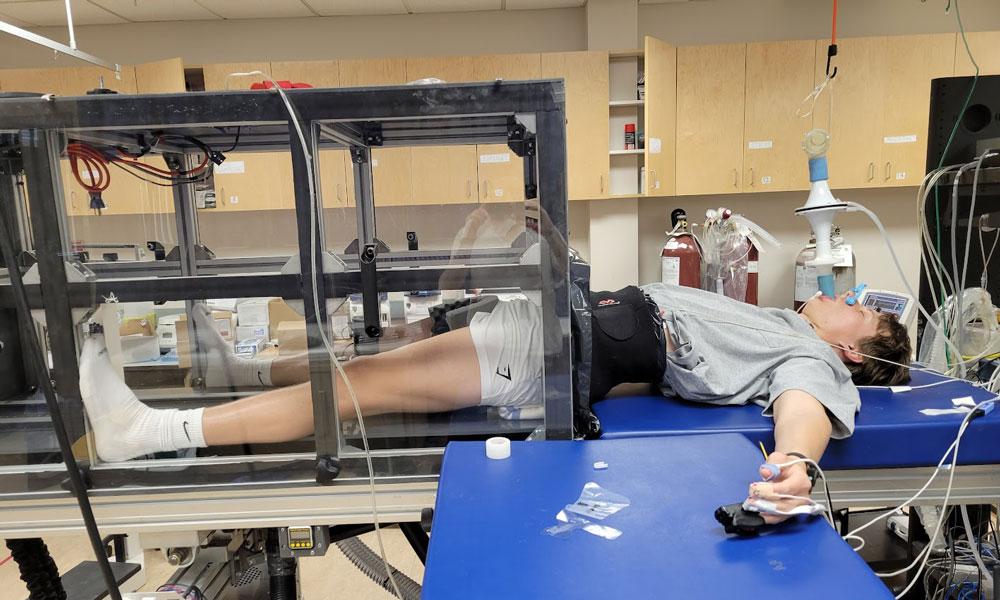

Here, Monteleone lies in a lower body negative pressure chamber. This is used to simulate blood loss and physiologically stress the body’s cardiovascular system. Reflex increases in heart rate and blood pressure can be manipulated and observed in a well-controlled manner, making the device an important tool for physiological research.

He adds that by mimicking states like hypoxia or hypothermia in the lab, “we gain normative data from healthy humans. This is compared to data from selected clinical populations who are studied by our collaborators at Vancouver General Hospital, especially those with hypoxic brain injury following a cardiac arrest.”

This work has already led to a better understanding of the brain’s normal physiological responses to changes in oxygen in healthy humans as well as patients. “We’re one of the few groups in the world doing this kind of research, where we compare and translate our results from healthy humans directly to clinical populations.”

In another study, Dr. Ainslie is doing the first work with humans to simulate what happens in avalanche conditions—a relevant issue as growing numbers of people venture into BC’s backcountry for snowmobiling, skiing and heli-skiing adventures.

Getting caught in an avalanche can lead to “Triple H Syndrome”; when there is no fresh air, carbon dioxide builds up (hypercapnia), there is progressively low oxygen (hypoxia) and core body temperature (hypothermia) drops.

“Understanding how humans respond to this kind of stress will help inform survival times and potential treatment strategies.”

Some of the high-altitude research work the team conducted in La Rinconada, Peru. Photo courtesy of Axel Pittet.

Researching such extremes of human physiology often involves going to literal extremes. Dr. Ainslie’s work has taken him from the mountainous regions of Asia, South America and Africa to study acclimatization and adaptation in Indigenous populations to high altitude. Extensive research has also been conducted in elite free divers in Europe.

But it’s all in pursuit of the larger scientific picture to understand extreme physiology and potentially help people better assess, treat or survive illness. “If you want to ask bigger scientific questions, you have to be more ambitious, and it certainly takes more commitment from volunteers and an incredible team to do that.”

Dr. Ainslie adds: “I feel extremely fortunate to have this here at UBC Okanagan and via our local, national and international collaborators. The future implications of this work will be directed to understanding the impacts of climate instability on humans, especially in at-risk populations.”

Monteleone agrees. He points to the professionalism and passion that Dr. Ainslie and his team have for the subject matter, which keeps him coming back to the lab day after day.

“I don’t think I could have had the experience with Dr. Ainslie anywhere else. His lab is a great place to enhance my exposure and understanding of how labs work at universities and research-intensive hospitals. I love being in that environment and being part of ground-breaking research.”

*Main image courtesy of Lizzy Fowler.