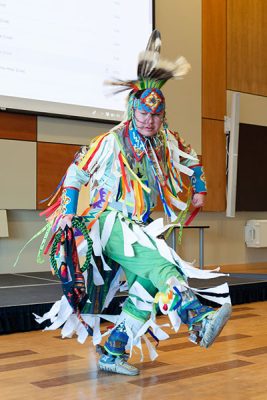

NOT EVERYONE EMBRACES LIFE LIKE COLTON STERLING-MOSES. The 22-year old from the Nlaka’pamux and Syilx Nations is optimistic about the future, enthusiastic about traditional dance and has the generous life goal of helping those in need. Now in college, he credits his success to the support of his mother and his community.

Sterling-Moses sees himself as fortunate and wants to pay it forward.

“I’m a minority within a minority,” he says, explaining that he is an Indigenous person living with autism. “I have a responsibility to bring awareness to people like myself and I want to make a difference.”

That’s why Sterling-Moses is engaged with UBC Okanagan’s Transitioning Youth with Disabilities and Empowerment (TYDE) project, where he contributes both input as a self-advocate — representing individuals with disabilities — and as a trial user of the TYDE service.

The young advocate is midway through his undergraduate training at the Nicola Valley Institute of Technology to become a social worker. It’s his way of giving back to the community that supported him along the way.

“Everyone needs help and the key is to ask for it.”

Although Sterling-Moses’ path has been relatively smooth, he notes that there have been bumps along the way, including overcoming shyness and determining what type of work would be most fulfilling. Spending time as a participant and mentor with the youth community group IndigenEYEZ ultimately helped Sterling-Moses discover a deep empathy for young people. He advises those who are struggling to keep trying, and believes that advocacy for people with disabilities is a priority.

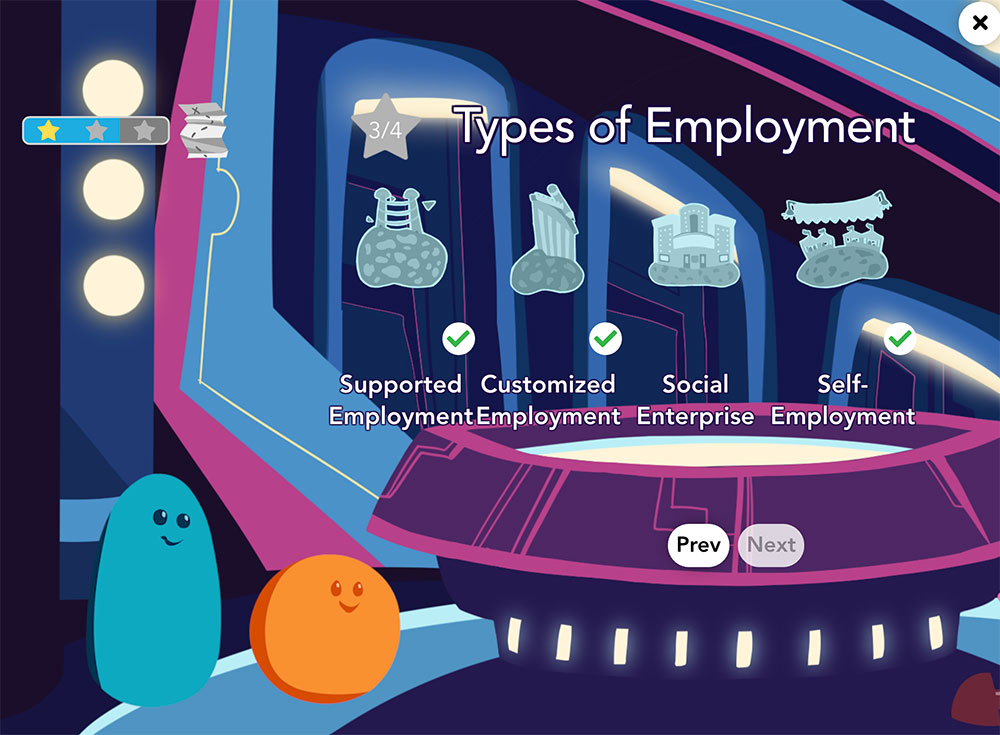

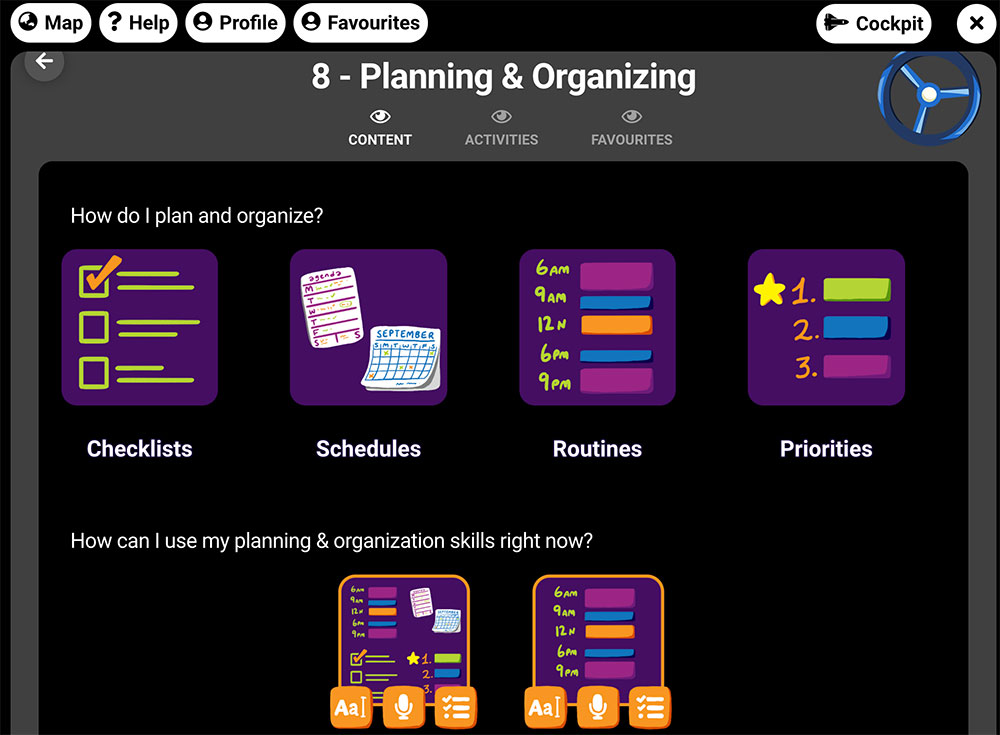

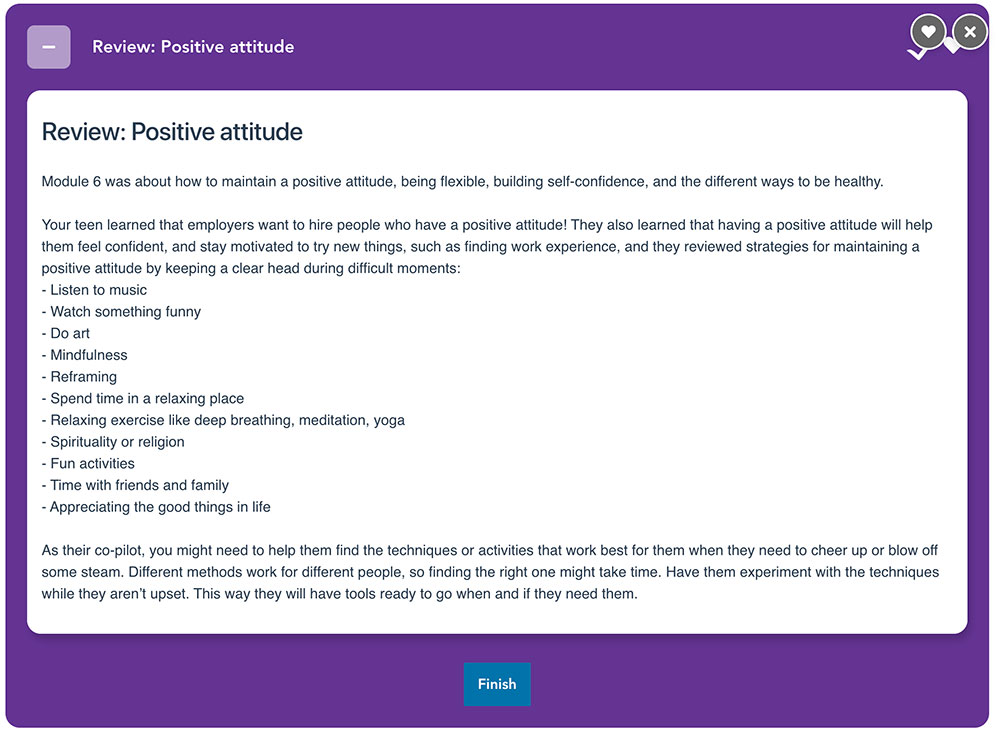

Rachelle Hole, an associate professor at UBC Okanagan’s School of Social Work and principal investigator on the TYDE project, explains that the platform’s interactive online curriculum integrates step-based learning with achievable milestones. “As a self-directed platform, its purpose is employment success for youth with developmental disabilities.”

Colton Sterling-Moses

In Sterling-Moses’ case, even though he had an emotional and educational support system to help him through his teens, he says he could have benefited from a program like TYDE.

“We need to ensure that youth have the tools they need to succeed,” he says. “And TYDE should be included in that kit.”

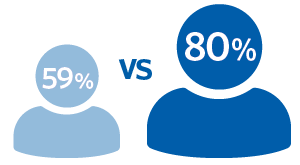

TYDE was developed in response to the disheartening reality that only 60 per cent of Canadians with disabilities are employed compared to 80 per cent of those without. And this number plummets to 22 per cent for individuals with an intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder. What’s more, people with disabilities usually work fewer hours and for less pay than their colleagues without disabilities.

Hole aims to change these statistics. She points out that such employment disparities are at odds with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which recognizes “the right of persons with disabilities to work on an equal basis with others…in a work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities.”

In Canada, this applies to more than six million people, or one in six.

Equity Matters (Stats Can, 2017)

Number of Canadians living with a disability

Employment rate for Canadians with a disability compared to those without

Employment challenges faced by persons with a disability

“We’re dedicated to addressing the low employment status for people with disabilities,” Hole says. “Through our program, we can empower this population to be independent and have self-determination. Not only does this goal align with BC’s citizenship priorities, but it’s also a mandate for provincial school boards, community organizations and caregivers.”

It’s no surprise that having a steady job improves one’s outlook, and this could be even more rewarding to someone with a disability.

“Having a job can be life-changing for people with developmental disabilities,” says Hole. “It improves self-esteem and sense of self-worth, which in turn will enhance their relationships and quality of life. People with disabilities are no different than those without; they want to have a life purpose.”

Advocating for those who have diverse abilities or backgrounds has been Hole’s focus for more than two decades. As a graduate student at UBC, she studied the association between hearing loss and identity, and prior to that she worked as an ally in the deaf community for over 20 years.

“I’ve always been passionate about social justice issues and in particular, I’ve questioned and challenged the stigma around disabilities,” explains Hole, who is also co-director of the Canadian Institute for Inclusion and Citizenship — Canada’s first university-based research centre focussed on inclusion and citizenship policy for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Currently, Hole is researching practices that promote social inclusion and equity for people with disabilities. Collaboration with the community is key to this process.

“By partnering with community members at the outset, we gain knowledge and an understanding of their issues and challenges, which is critical to our work.

“By giving a voice to those who seek change, it empowers their success.”

How TYDE Works

Like many online learning platforms, the TYDE program offers interactive step-based learning with integrated milestones.

The first few modules focus on general topics like the benefits of having a job and employee rights, followed by more tailored content exploring different types of jobs and employee responsibilities. The final modules discuss how to get and keep a job.

For Hole, awareness and choice are the most important pieces.

“Woven throughout the modules is the importance of self-determination, with the ultimate goal of contributing to the development of confident and empowered youth,” she says. “Being able to make choices and stand behind them is the strongest predictor of employment success for this group.”

Hole and her team chose to target young teens for the program, with the philosophy that timing is everything.

“Previous studies have shown that early intervention during high school is key. Factors like access to inclusive education and early work experiences can significantly improve future employment outcomes.”

Hole notes that parents play a key role in their youth’s success, which is why the platform has modules for both groups.

“Ours is one of the only interventions that purposefully includes parents and focuses on them and their child as a duo,” she says. “In this way, parents discover the strengths of their youth and how to best support them, while the teen can learn about themselves, their passions and abilities.

“It’s amazing to watch parents and their children’s belief in their capabilities grow.”

A Game Changer

“The TYDE project is a game-changer,” says Shameera Rosal, a self-advocate consultant with TYDE. “I would have embraced this program if it was available when I was a teen. It would have helped me realize sooner that I have skills and I can work.”

Rosal, a 23-year old arts student at UBCO, earned a silver medal in swimming at the 2018 Special Olympics. This competitive nature pushes her to not only strive for physical goals but also academic and personal achievements.

“I’ve always been very much into academics,” she says, acknowledging that living with a disability and moving into a working world was challenging. “It wasn’t easy to figure out what to do after high school, especially as I didn’t know what kind of work was possible and how to achieve success.”

Shameera Rosal pictured at her part-time job.

But, university beckoned to Rosal, as did finding a job. While taking classes she has also been working part-time, first at a fast food restaurant and then at a local gym. Her perspective and experience have made her an excellent advisor for the TYDE project.

Hole says that the input from self-advocates like Rosal and Sterling-Moses is an integral and vital part of TYDE.

“We want to deliver the most effective intervention we can, and we can only achieve this through input from our diverse community.”

For her part, Rosal enjoys working with the TYDE group. “This project aligns with my self-advocacy goals. I want people with diversity to know that they can do anything they want. I don’t have to convince people I’m capable; they see it. I’d like everyone to feel this way.”

The optimism, enthusiasm and determination of both Sterling-Moses and Rosal is infectious, making them ideal role models. They want employers and community members to believe in the capability of people with disabilities — but more importantly, they want these individuals to believe in themselves.

“I want people with diversity to know that they can do anything they want.”

“Don’t close yourself off from the world. If you want change, it has to start with you first,” says Rosal.

Hole notes that self-advocates have above average attendance, a low turnover rate and evidence shows that businesses that offer employment opportunities have higher staff morale and are seen more favourably than their competitors.

“The research is very clear,” says Hole. “Supporting self-advocates as they transition from school to adult life and giving them opportunities to contribute through meaningful work has enormous benefits for both the individual and the businesses they work for.”

Improving Lives with TYDE

For more than 20 years, Nathan Ngieng has been shepherding adolescents with disabilities through the school system and says there’s a ‘service cliff’ once they graduate.

“Traditionally, there’s been a lack of preparing young people with disabilities for employment or post-secondary education,” says Ngieng, who is the director of instruction at the Abbotsford School District and president-elect of the BC Council of Administrators of Inclusive Support in Education. “We’ve been all over the map in terms of how we prepare them for this.”

He agrees that the TYDE project is hitting the mark and is unique in its approach of including caregivers in the process.

“The TYDE project is an interdisciplinary network of partners committed to improving the employment outcomes for transitioning youth with developmental disabilities in BC,” explains Hole.

Funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the project includes three universities, nine community organizations, two government partners, and several paid self-advocate consultants in this collaboration.

“This team has knowledge, expertise and experience in a range of areas including behavioural neurosciences, public health, education, psychology and policy development,” adds Hole.

Learn more about

Ngieng is enthusiastic about the project, saying: “This is a great example of multiple partners coming together, which we know is extremely important for families and youth.”

Ensuring an Indigenous perspective in the group was also important. This is where Sue Sterling-Bur of the Nlakap’mux and Sto:Lo Nations comes in. Hired as a research associate, Sterling-Bur’s role is to ensure that Indigenous rights are being honoured and culturally-safe content is provided. She is also reaching out to various communities, some in remote locations, and facilitating respectful relationships.

“We want to reach all people with disabilities and therefore the language should be inclusive,” she says.

Sterling-Bur agrees that TYDE is a trendsetter by including an Indigenous voice from the beginning of the project. “I think all research projects should be connected to the Indigenous communities where the work is conducted,” she suggests.

“It’s exciting to see inclusive research projects like this.”