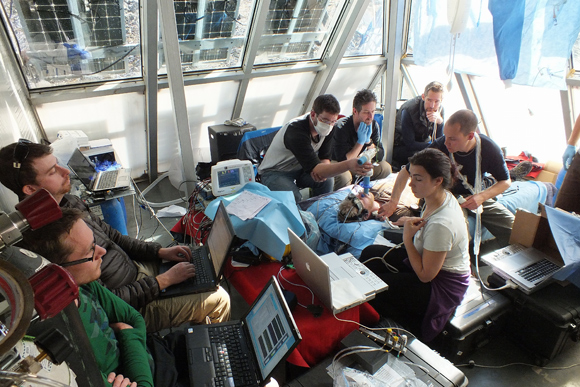

Team members of Everest 2012: UBC’s International Research Expedition, conduct one of several human health experiments at Mount Everest’s Pyramid Lab.

UBC-led expedition examined high-altitude oxygen deprivation, blood flow

UBC scientists on Thursday night told a Penticton audience about some of their early health-study findings from last spring’s international research expedition to Mount Everest.

The Pyramid Laboratory seen in winter.

Faculty members from UBC, Okanagan College and six other countries made the ground-breaking trek to the Pyramid Lab near Everest Base Camp to study the effects of hypoxia – oxygen deprivation – and lower blood flow the brain and vital organs at high altitude. The symptoms are similar to those suffering from chronic heart and respiratory illnesses and strokes.

The scientists also studied the causes of sleep apnea, a common affliction that routinely affects both visitors and high-altitude residents.

“We are very close to discovering what causes sleep apnea,” Philip Ainslie, associate professor with UBC’s Okanagan campus School of Health and Exercise Sciences and Canada Research Chair in cerebrovascular physiology, told the gathering at Okanagan College’s Penticton campus.

The next phase of interpreting research data from the six-week expedition will be presented in papers delivered to an international conference on hypoxia in Lake Louise in February 2013, Ainslie said.

A panel of scientists and students who went to Everest presented some of their preliminary findings for the first time in a public forum.

Nia Lewis, a post-doctoral fellow at UBC, made some astounding findings in measuring the human circulatory system. The 25-member expedition used themselves as study subjects, conducting baseline research at UBC for a month before departing for Nepal.

“Despite the bouts of mountain sickness and sleep apnea we all suffered, it became apparent that after two weeks, the human body was successfully adapting to the high altitudes,” Lewis said. Blood vessels among the expedition members were expanding like rubber tubes to accommodate higher flows of oxygen-rich blood to the brain and vital organs.

It was the first time the human circulatory system was studied for changes in blood flow at high altitude.

Greg DuManoir, professor of human kinesiology at Okanagan College and a sessional instructor at UBC, said the numerous research projects he participated in at Everest are benefiting his students. “There is such a wealth of data at my fingertips that I can use to develop new course content for the next 10 years.”

Two UBC students on the Everest expedition said the experience was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity they will never forget.

PhD student Jon Smirl at UBC’s School of Health and Exercise Science said the research opportunity at Everest will fulfill his ambition to finish his doctorate.

Ryan Hoiland, a fourth-year student, said the Everest experience has convinced him that he should follow a path of academic research well beyond his undergraduate degree.

“I’m 21 years old and I know that whatever else I do with my life, nothing will compare to the experienced I had at Everest,” said Hoiland. “I am so lucky and thankful for having been a part of this.”

A view of the majestic Himalayas.

— 30 —