MUCH MORE THAN MERLOT IS BEING HARVESTED from the vineyards dotting the landscape near UBC’s Okanagan campus.

The Okanagan Valley is fertile ground for research in an array of academic disciplines—from biology and the microbial makeup of the soil, to engineering more sustainable operations and managing collaborations to support growth.

Researchers are being drawn to this regional cluster of viticulture and wine production because of the unique and meaningful connections with growers and producers. The local industry is keen to collaborate with the university, opening their doors to applied research in vineyards and tasting rooms throughout the valley.

The result has been innovation with the potential to change practice locally and branch out with international effect.

Digging Out the Answers: Miranda Hart

For Associate Professor Miranda Hart, conservation is at the root of all her work—even if you can’t see the creatures she is interested in preserving.

For Associate Professor Miranda Hart, conservation is at the root of all her work—even if you can’t see the creatures she is interested in preserving.

As a soil microbiologist, Hart studies the symbiotic relationship between plants and root micro-organisms. The field naturally gravitates to researching agricultural applications, as food production carries a heavy environmental footprint on soil.

“Coming to the Okanagan, it just makes sense to work with grape vines,” she explains. “The growers and wine industry are really young in BC and Canada. Most of these people haven’t learned from their parents how to grow grapes; they are the generation that is learning to be viticulturists.”

Hart met growers while working with researchers at the Summerland Research and Development Centre, a federally operated facility an hour away from UBC’s Okanagan campus, which focuses on building resilient horticultural production systems. Partners were eager to work with Hart and her students.

“They are open and progressive, willing to try innovative things to make their operations sustainable,” Hart says. “They really care about the soils. I think you could say all good farmers are concerned with soil, but the grape growers care about the microbes—they want to take care of them.”

She is looking at the benefits of introducing native plants like sagebrush between the vines.

“We’re investigating that plant biodiversity might be a very powerful tool for growers to wean them off herbicides, pesticides and fungicides. It helps the plants help themselves,” she says.

“I want my work to be useful. I want to know that my research is making things better.”

Hart is also looking at the use of commercial microbial inoculants—whether they help, or hinder, local soil microbes.

What keeps her going is the opportunity to change agricultural practices for generations to come.

“When I was a master’s student, I worked on a reforestation project. When the forest companies adopted our recommendations, it was so satisfying to help change forestry practices,” Hart recalls. “I want to do this for viticulture, too.

“I want my work to be useful. I want to know that my research is making things better, making viticulture, making agriculture better. I can’t imagine not working with industry.”

Industry Impact: UBC-KEDGE

Cooperation, identity and quality.

Those are three critical characteristics of a successful wine region, and at the heart of work underway by the UBC-KEDGE Wine Industry Collaboration.

In 2012, UBC’s Faculty of Management and Regional Socio-Economic Development Institute of Canada partnered with KEDGE Business School in Bordeaux, France to work closely with the BC wine industry to address its strategic concerns.

“We’re trying to bring international expertise to bear on some of the issues that our region is facing, so that we can have an impact on the innovation and socio-economic development of the region,” says Professor Roger Sugden, the lead UBC researcher on the project, which is partially funded by Western Economic Development.

Scholars with the UBC-KEDGE research team take a creative approach to exhibitions, dialogues and annual activities to foster safe and inspiring spaces for industry players and the public to share their perspectives, reflect, deliberate and explore ideas. A “Wine Leaders Forum” is organized each year to bring together British Columbia winery owners and principals with international wine experts in a retreat-style setting, where relationships can progress, knowledge can be shared and strategic challenges can be explored.

“We’re trying to bring international expertise to bear on some of the issues that our region is facing.”

In 2017, an exhibition called Refractions: Appreciating the British Columbia wine territory was held at multiple locations throughout the province to encourage residents and visitors to explore the BC wine territory identity and its impact on regional development. Supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the exhibition featured archival and contemporary photographs, poems, quotes, art installations and a collage—a collection initially presented at the Wine Leaders Forum.

“We use visual elements such as photos and collage to stimulate thinking and discussion,” says Sugden. “We hope that through these activities, people will deepen their appreciation of the wine territory and their understanding of the different elements that contribute to its success.”

UBC-KEDGE Wine Industry Collaboration has presented public talks featuring academic research on a variety of topics, and a task force on wine labelling has provided recommendations for public policy changes.

All the work done to date involves significant academic and industry research, conducted by UBC-KEDGE. That independent investigation is where industry derives particular value.

Waste Not: Biological Solutions Laboratory

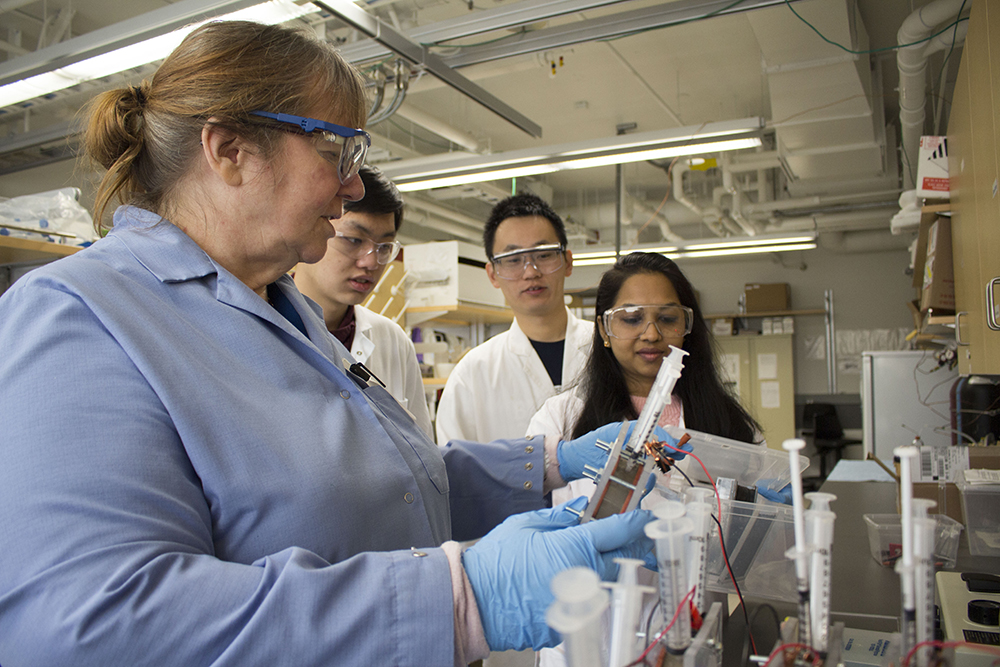

After spending a career studying industrial wastewater, engineering Professor Deborah Roberts has found a unique research opportunity in the Okanagan.

Researchers in her Biological Solutions Laboratory at UBC’s Okanagan campus have found a way to turn winery wastewater into power.

“Winery wastewater is very biodegradable. It’s a great source of food for micro-organisms, which take the chemical energy in the waste and convert it to electrical energy,” Roberts says.

“We know we’re not going to run the world off wastewater. There are losses in the system, but it’s better than pumping energy into treating the water.”

Using microbial fuel cell technology, Roberts and her team are converting energy from organic waste into electrical energy—making wastewater that was once a hindrance from winery operations into an advantage.

Managing wastewater can be an energy intensive process, making the process out of reach for many small businesses. This new technology may make sustainable operations much more accessible.

“We’re finding decent power production and really good removal of the compounds at the lab scale. Now we’re looking at what is the best way to do it at a full scale,” Roberts explains.

Wine producers are seeking differentiators like green and sustainable operations. With global wine production expected to grow to more than 30 billion litres by 2020, Roberts sees microbial fuel cell technology as one opportunity for winery owners and operators.

Having spent several years in Texas researching the outputs of the oil and petro-chemical industries, she understands how important it is to collaborate with those who are directly involved in the operations. The same holds true with Okanagan wine growers.

“They have expertise that I don’t have,” she explains. “The collaborator understands the economic stressors around how much they can afford to invest in something like this. The industrial partner has to be part of the collaboration.”